Article

Roundtable Chapter 1 – The One Where the Device Was Only Half the Story

On May 25, 2021, Bernhard Kappe and Randy Horton spoke at Celegence’s Medical Device Virtual Summit 2021 on the topic of “Patient Engagement and Software as Medical Device (SaMD): The Coming of Medical-Grade Lifestyle Devices.”

Executive Summary

Traditional medical device manufacturers have mastered difficult domains such as distribution, device and integrity, and privacy. But their products generally don’t inspire a level of passion among patients and clinicians that can drive exceptional levels of adoption and adherence.

In contrast, consumer device manufacturers don’t know how to create safe and effective regulated medical devices that achieve stellar market success. What they do know is how to create products that people use constantly because they love them, have an emotional affinity for them, find them endlessly fascinating, find them useful, and sometimes even can’t imagine life without them.

By blending the best-of-breed capabilities of medical device manufacturers and consuming device manufacturers, a new class of devices is possible: Medical-grade lifestyle devices. When combined with remote care services, medical-grade lifestyle devices have the potential to drive major advances in healthcare costs and outcomes.

In this talk, we look into this idea in more depth, examine some emerging success stories, and discuss a variety of the challenges that will have to be overcome by industry leaders to cross this chasm. Bernhard Kappe and Randy Horton present their points of view, and provide context to explain how SaMD, digital therapeutics (DTx), and connected medical devices can play a huge role in this undertaking.

Following the talk, there is a Q&A session where event attendees posed a number of interesting and insightful questions.

If your question was not asked…feel free to contact us.

You can watch the video here, or read the transcript of this talk and see the slides by scrolling down.

Randy:

Good morning. I’m Randy Horton, VP of Solutions and Partnerships at Orthogonal.

Bernhard:

And I’m Bernhard Kappe, the Founder and CEO of Orthogonal.

Randy:

Orthogonal is a product development consulting firm. We work with medical device manufacturers to help them accelerate their development of Software as a Medical Device (SaMD), Digital Therapeutics (DTx), and connected medical devices.

We’ll be presenting today on the topic of Patient Engagement and Connected Medical Devices. We want to thank all of you for joining us here today. We appreciate you taking time out of your busy day and look forward to interacting with you in the Q&A. I’d also like to add that Bernhard and I are both fully vaccinated, so we are being quite responsible while enjoying the fact that we’re able to co-present together for the first time in over a year.

Bernhard:

So thanks to all of you for watching, and thank you also to the Celegence team for inviting us to be here today.

Randy:

All right, Bernard, let’s get rolling.

When people think of state-of-the-art healthcare in this country, often what comes to mind are big gleaming buildings with big pieces of machinery inside big iron, MRIs, radiation therapy machines that do very powerful things, but they’re highly controlled environments. And they depend on operating in highly controlled environments. Patients are essentially summoned to these devices and do exactly what a tech tells them at the order of a doctor in order to get the benefits of the devices. And while these are really remarkable things, in many ways they make up a fairly limited part of what impacts health care costs and outcomes in this country today.

As you know, the exploding costs of care and the growing demands for care are largely related to things that happen in our bodies day to day, things that we have some influence over in our normal lives outside of the hospital, outside of the doctor’s office.

We’re talking about chronic disease conditions like COPD, diabetes, and hypertension, and the more we can deal with these things through early diagnosis, ongoing monitoring and smaller, more effective doses of treatment, the more we can prevent illness and delay disease, or even defeat it. And the shift of healthcare out of hospitals and into the home that was accelerated by COVID-19, has really accelerated this because a lot more people are asking why does a patient need to come in to see a doctor or a nurse, a hands on, at any given time? Is it really that important that they come in? But engaging people in their day-to-day lives, when your doctor and care team aren’t physically present, is a very different healthcare challenge than treating people in outpatient or inpatient settings, the home, the car, the office, or the supermarket. A medical professional isn’t standing there telling you: It’s time to get up. It’s time to go to sleep. You should really eat this and not that.

Have you taken your medicine?

You’re on your own for those things. And while you may know what the right thing to do is, that doesn’t necessarily mean you’re going to do it. After all, we’re only human.

So patient engagement is an idea that’s been around for a while. It’s about getting people involved in their own care and giving them the tools and the nudges to move towards better behaviors and away from the worst ones by helping them help themselves.

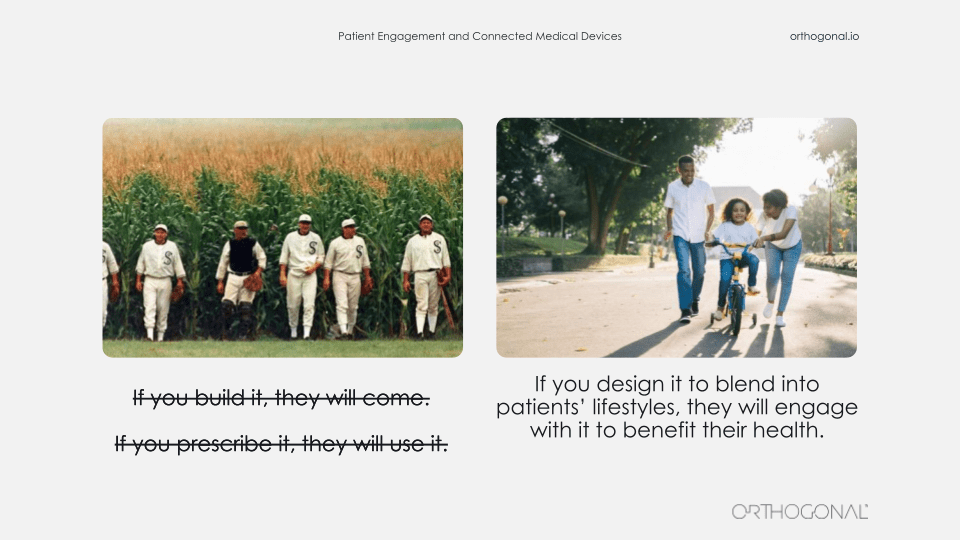

There’s a famous line from the baseball movie, Field of Dreams, “If you build it, they will come.” So if you were going to translate that to medical devices, you might say, “If you prescribe it, they will use it.”

But the truth is that the Field of Dreams principle really does not apply with medical devices in patient engagement at the home. If you prescribe it, they may not engage. Or if they do engage, it may not be in the exact way you intended. So most likely you should just assume they won’t engage. Just look at online classrooms for kids who are at home because of COVID learning. If you put a child in a Zoom classroom, that doesn’t mean they’re engaged. It doesn’t mean they’re learning. Those are two very different things between logging in and actually being a part of the classroom and many people have seen that lately.

In the same way, if you’re going to just drop a medical device into somebody’s lap at home, you can’t magically expect that they’re going to use it the way it’s intended and get every last ounce of value out of it. So as a result, we don’t have to just bring people to devices, we have to bring the devices to people. We have to let the devices fit into the patient’s lifestyle and not vice-versa. So maybe what you could say instead would be, “If you design it to blend into people’s lifestyles, they will engage with it to their benefit.”

This is part of something we’ve been talking about in some writing we’ve been doing with our colleague, Adrian Pittman, who recently moved from Google to LinkedIn. The idea we’ve been writing about is that device manufacturers, in some ways, are going to be shifting from being manufacturers of medical devices to manufacturers of medical-grade lifestyle devices. And that’s a very different thing.

There’s a lot of examples of lifestyle devices not in healthcare. Things that you use every day or frequently. Things that you really count on.

Usually, you also don’t want to think about them. You just want them to work. Paperclips. Post-It notes, your coffee pot, your Internet router. All of these… when they’re not there, or they’re not functioning, it’s annoying. But other than that, you just expect them to blend into the background.

Bernhard:

“Dear Mom and Dad, You can have my smartphone when you pry it from my cold dead fingers. Sincerely, your teenager.”

I’m the father of two teenage daughters and while those aren’t their exact words, that is exactly how they feel.

This is a device that really is a home run in fitting into our lifestyle and just working the way we need it to do. It’s addictive. Why is that? Why is it so woven into our lives?

Well, it’s simple. It’s the world at your fingertips in your pocket, instantaneously. Your friends, your work, your information, devices, your house, your car, things you haven’t even thought of yet. It’s become an all-purpose tool that is both an extension of ourselves and our connections to the world as phones, texting, messaging tools, access to the world’s text and visual library.

How did this get here? It’s not really something that just magically appeared.

It’s actually part of a larger trend which is the concept of software eating the world. It’s something that Marc Andreessen coined in 2011. He was the founder of Netscape and a partner in the VC firm, Andreessen Horowitz. He wrote a famous article about this in the Wall Street Journal and his observation was that software is eating the world in all sectors and in the future, every company will become a software company.

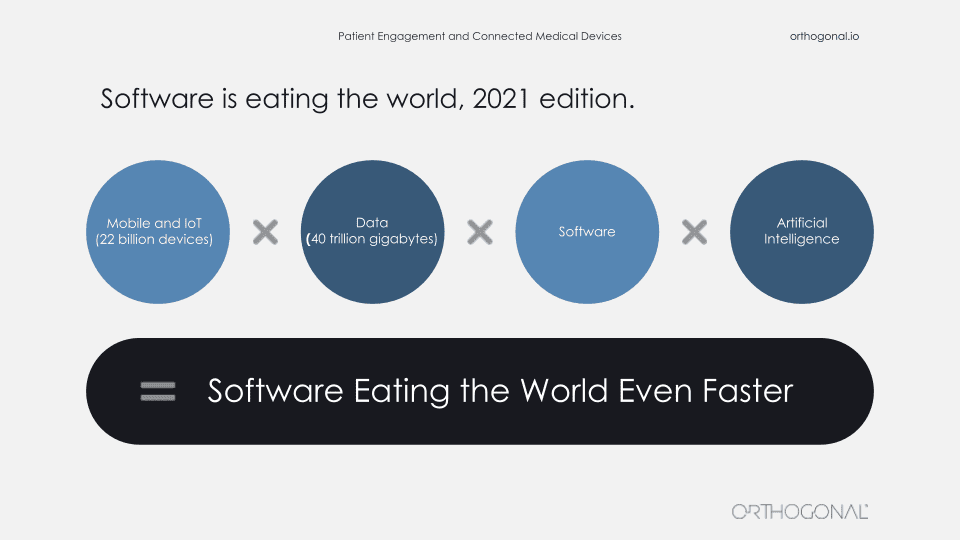

This was pretty controversial at the time, but it no longer is. Really, this is what’s been happening and smartphones are an extension of that. What’s been happening is all of these things have been getting faster, better, smarter. If you look at a smartphone from the first iPhone to smartphones, now they are significantly faster, significantly better and more connected. It’s not just mobile, it’s all hardware and software that is getting faster and better.

There are more connected devices. There are more things you can access and control such as IoT, cloud computing, and all the network effects that come out of that. And all of that means that there is also more data, more data that you can work with more data that you can consume, but also more data about you, about what you’re doing, about how you’re behaving, about what you like and how you respond to stimuli and how products are performing in doing those things for you.

That’s where AI comes in as well. AI can take all of that data and generate algorithms and generate things for you to react to and to consume and to pay attention to. You put all of those things together and software is eating the world even faster. There’s a really good illustration of this in a recent Wall Street Journal review of the Apple AirPods Pro. It’s not the first review. It’s the second review a year after the initial review. It’s not a review of the new AirPods Pro, it’s a new review of the same AirPods Pro, and it’s a much better review than the first review was.

Why is that? Well, better software. Apple kept collecting data and feedback and continued to improve the software to the point where the journal did a whole new review of the product and gave it rave reviews. All of that is collecting data in AI and using software to improve the product.

Randy:

So, usually when we talk about a competitor in our industry, what we’re talking about is another device company that’s made another device performing the same clinical function and life is good when your device is cheaper and more effective than their device. But when you’re trying to engage with patients in their daily lives, we have a whole new class of competition. And most of that competition really has nothing to do with you or your medical device, or even the patient’s health.

Patients aren’t under stimulated. They’re not bored. They’re not waiting at home for someone to drop an app on their phone that’s going to engage them. Really we’re in a full all-out battle for the attention of our patients. And right now, the battle is being fought between the new tweet from Krispy Kreme about the latest item on their menu and your glucometer app’s flashing red warning sign.

A few years ago, I came across this article about the last remaining patients in America still using an iron lung. The iron lung is really an incredible device. I mean, just look at the picture here. It’s a workhorse of science and engineering that’s lasted decades.

And it’s something that the medical device sector, I think, has illustrated with something that we’re really good at. We build safe and effective devices that are engineered and built to work as promised.

But I’m guessing that nobody would say that the iron lung is very good at patient engagement. The science fiction writer, William Gibson famously said, “The future is already here. It’s just not evenly distributed.” And the picture we’re painting today doesn’t exist in a single success story, but all the elements of what patient engagement with connected medical devices look like can already be found in different places.

So an act of fusion imagination, we can envision what it might look like when we are successful at this. We’re going to be borrowing elements from consumer electronics, the internet of things, learning from Facebook and Google and Amazon and Spotify. The people who make Pokemon, that franchise. They clearly know how to engage people in different mediums over long periods of time. And yes, there are some early success stories that we’d like to point out from the medical device space. One great example of embedding a therapeutic device in people’s lives is Akili.

If you haven’t heard of them, they have the first FDA approved prescription video game. I’ll say that again. It’s a prescription video game. And the reason you need a prescription for it is it’s actually a covert treatment for children who have ADHD. So I’m asking you, what’s easier in terms of patient engagement, dragging your kid on a sunny day to some therapy session in an office, or giving them permission when they ask you to play a video game that just happens to be therapeutic.

Akili has done the equivalent of hiding vegetables in food so the kids don’t even know they’re eating the vegetables. They just know they love the food.

Two great examples of bringing medical devices into people’s lives where they live, not in the home, but into places that they frequent. On the left, it’s a device that’s been brought into a barber shop and on the right you’ll see many of these devices in pharmacies and community centers around America. The one on the left is from Cedar Sinai. They were trying to tackle the problem of hypertension among African-American men. And they decided that their efforts were better spent rather than trying to get African-American men to come to the clinic, to be diagnosed and treated for hypertension, that they would go to where they could find the patients they needed to reach.

So they teamed up with barber shops across LA and embedded in them these devices, which are a combination of a blood pressure cuff and a telemedicine station. And they brought pharmacists physically to recruit patients to participate in this study. And then when people return for later haircuts, the barber is trained to essentially nudge the patient, “Before you get a haircut, would you mind sitting down, doing another blood pressure check and if you need, talking to somebody remotely?” So this is bringing a device to people where they are in their lives to get them to use it.

Higi’s done a very similar thing. This machine on the right is something that you can step up to and it takes some basic vitals, shows you what your vitals are, and send them back to your doctor. It allows these key vitals to be taken in a professional, consistent way without having people come into the doctor’s office. You sit down at one of these at your neighborhood pharmacy and do it for a couple of minutes while picking up a prescription or your gallon of milk.

The last example we want to talk about is from Quidel, one of our clients. They make point of care diagnostics for infectious diseases, including COVID-19. On the left is the Sophia Q device. That’s a cornerstone of their product suite. You insert an asset cartridge into it for a specific infectious disease and it spits out a test result. It’s hardware is similar to a video game console. Quidel manufactures the console and then they make lots and lots of game cartridges that they sell, each of which can be for a different test. So the Sophia Q machine can be interpreted for lots of different infectious disease tests.

This machine is not a big iron. You can call it maybe medium iron. But it’s certainly a substantial piece of lab equipment and it’s not something that you’re going to easily manufacture and distribute by the millions.

The device on the right is the Sophia Q. It’s Quidel’s newest member of their Sophia product lineup. It’s very similar to the Sophia Q. It can read the same immunoassay cartridges, but in this case, the images from the cartridges are captured and interpreted by an AI algorithm using a combination of this very small device, a smartphone and a cloud infrastructure.

So there’s a number of benefits to the Q system. They make it distinct from the Sophia Q. First, affordability. It’s a much smaller piece of hardware, which is much easier to manufacture and distribute.

Second, that also means you can scale up rapid manufacturing and actually produce and distribute millions of these devices.

Third, because the interpretation is based on an AI algorithm, the diagnosis can get smarter and better over time, just like the AirPods with their one year review.

And finally, mobility. When you combine smartphones, internet connectivity, and small devices together, you can start to embed infectious disease diagnostic tools in all kinds of settings that really weren’t feasible before, like nursing homes and clinics and pharmacies. Even though patients aren’t directly engaging with the Sophia Q, you’re bringing the healthcare system to where they are and bringing that important functions of the healthcare system to where people are in their lives and enabling them to get the care faster, better, and earlier.

Bernhard:

I would add to this that you can actually get direct patient engagement with these types of devices. Sophia Q is going to be integrated into telemedicine and probably be available as a home test in the future as well, at which point direct patient engagement is going to be a big part of it.

So if we look at product development outside of the medical space, it’s some remarkable stuff that’s going on there. What do people actually do outside of the medical device space and can we take some of that and bring that into the medical device space?

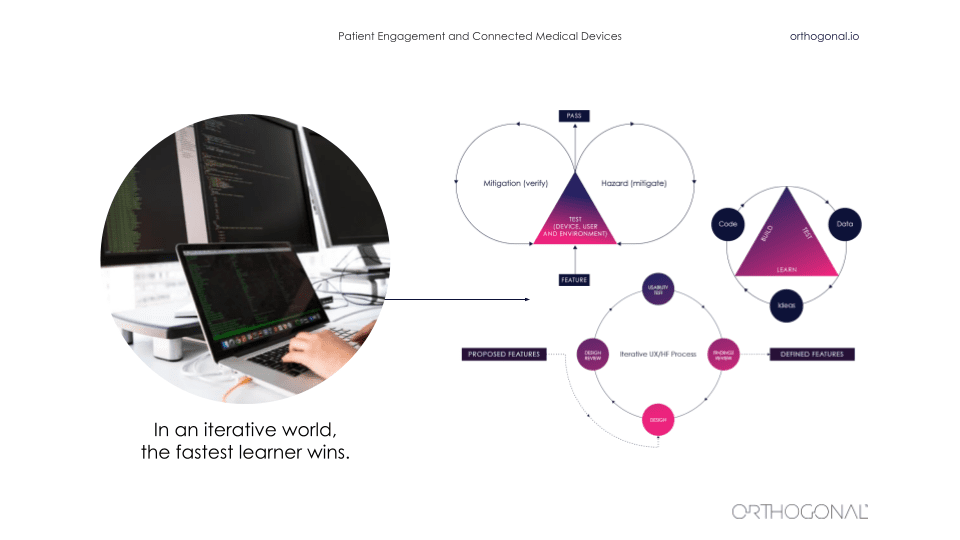

Outside of the medical device space, it is a very fast iterative world. As we saw before, things are changing quickly. It’s an ecosystem of interlocking parts that all magnify each other and amplify each other. And in that world, the fastest learner wins. There are a whole bunch of techniques from lean startup to design thinking that are there that can be used to iteratively improve a product.

It starts by thinking about the hypothesis and really validating your hypothesis as you go along and build out a business model and build out your company and its products. You’ve got to ask questions like, “Will this idea work? Will someone use it? Will someone pay for it? Will they buy it for me? Who is going to use it? And how will they value it?” All of these things are things that you can iteratively get feedback on and iteratively go out and test.

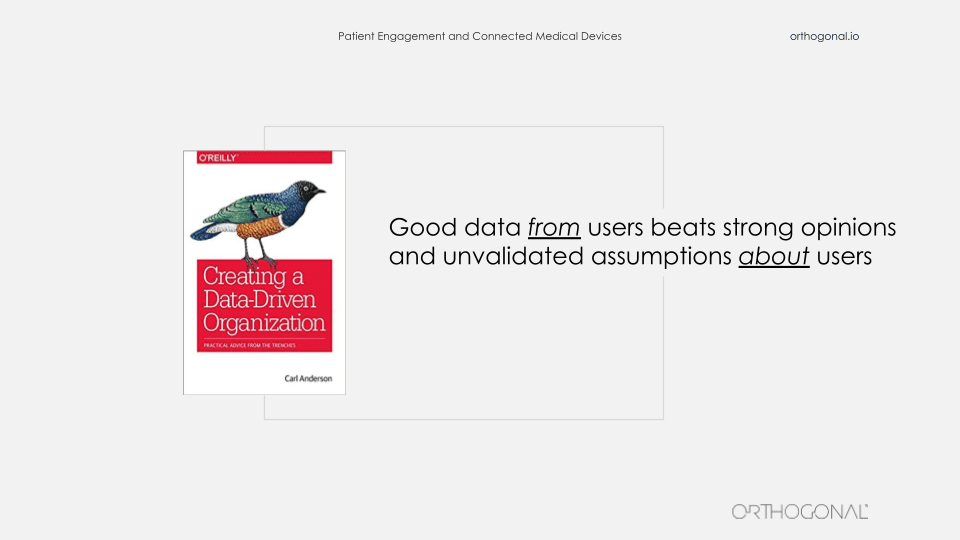

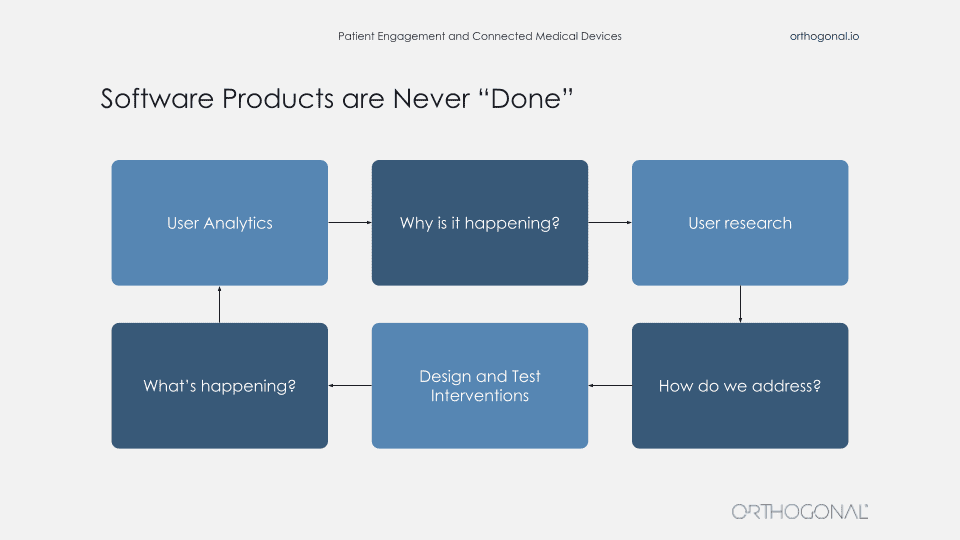

The thing that a lot of these companies do is actually go out there and talk to users and get data about users, and then go validate their assumptions with these users. When you’re building products in this way, your software products are never really done. There is a continuous fast feedback loop for getting data, using that data to make improvements, measuring that, and then continuing the cycle to continuously improve faster and faster.

So you’re always out there getting qualitative data about your users, what their needs are. You come up with solutions, you get feedback on that. And then you apply all these wonderful techniques like agile development, DevOps, and techniques to rapidly release new software. When you launch you now get feedback from that and you can continue to improve. You can even do things like A/B testing or multivariate testing to test the effects of new features. And then use that learning to go back into your qualitative methods and understand why people are doing this? And that can be done faster and faster and faster.

But I hear you cry, Randy?

Randy:

All right, Bernhard. So we can debate whether I’m the Greek chorus or the Debbie Downer in the room, but I’m going to ask a question that may be in the minds of a lot of the people watching this today:

It’s great if we can move faster, better, cheaper, and smarter with digital methods. But an insulin pump isn’t Snapchat, and a surgically implanted neurostimulator for the spine isn’t Netflix. These are regulated medical devices, and there’s a good reason they’re regulated. Nobody wants to be the next Theranos or Thalidomide.

So how do you mesh these worlds? Silicon Valley got famous for saying, “Let’s move fast and break things.” But in our world, if we move fast and break things, what we’re breaking is the human body. And if it’s a connected device, there’s a real risk we’re going to be doing that harm at scale. So how do you reconcile, move fast and break things with first, do no harm?

Bernhard:

You make a good point, Randy. But just because you have additional constraints does not mean that you can’t incorporate these fast feedback loop approaches. You just have to take those constraints into consideration.

Let me give you an example of that. One of the best practices for product development is this concept of Three User Thursdays. That means every Thursday you have three users, you’re in there and you’re getting feedback from your testing, et cetera. Basically, it’s a weekly cycle of user interactions, testing, and feedback. You can still do this kind of work and in fact, it’s an improvement over how we get feedback now. You just have to take a couple of things into consideration as you’re doing these user feedback sessions and this user testing. You need to take human factors into consideration as part of that. So you need to pay attention to potential use errors and how you would mitigate these.

You can get through and refine your mitigations for those use errors much better and much faster by using this technique than you would have by having human factors sessions every two, three, four months. You can just get many more cycles and much better refinement. So it’s a technique that works, and it just needs to take those constraints into consideration.

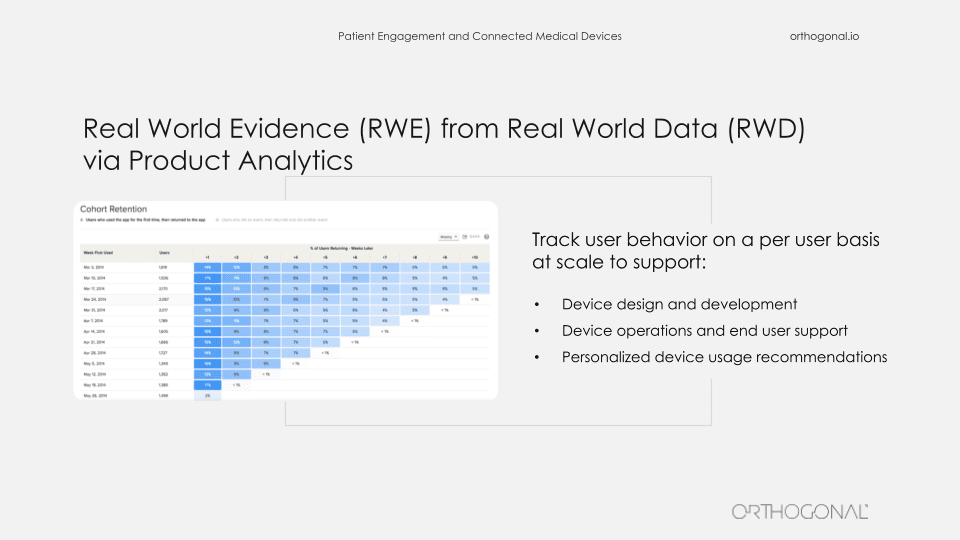

Similarly, product analytics, which is de rigueur in the rest of the world, isn’t really done much in the medical device space. But product analytics can tell you exactly how your users are behaving, and you can feed that into your qualitative research as to why they’re doing things. And you can also use this as part of your process for refining your product. The problem, of course, is that you have a constraint of HIPAA compliance needing to protect your patient’s data. But the reality is, there are product analytics products like Mixpanel that you can make HIPAA compliant, and where you can strip out patient identifiable information. And then you can use this to continue to improve your product.

In a similar way, all those software engineering best practices – agile development, test driven development, behavior driven design, testing automation, cloud to DevOps, self-healing infrastructure, just basic modularity – are great software practices that actually help you make products better, make them more robust and make them more reliable. These good practices are actually things that the FDA has blessed as standards that should be part of what you’re doing. They happen to allow you to do things faster than if you were doing things in an old waterfall way, but that doesn’t make them less reliable.

The problem that you do run into here, because of patient safety and because of the regulatory compliance issues, is around launching new features, right? So you do need to do extra work here. You need to take constraints into consideration.

In particular, you need to do risk analysis, determine the impact on effectiveness on claims, on intended use and on indications for use. But when you do that, then you can also leverage things like software segregation, as per IEC 62304 for higher risk areas so that you can then more freely iterate on low risk areas.

You can also potentially use the SaMD predetermined change control plan that the FDA introduced in their recent position paper on AI in medical devices. You can leverage real-world data for additional claims and even if you can’t do AB testing the way you might in another product, you can do canary testing, which is a form of A/B testing, where you have a new version that gets released to a small subset while the rest of the people are using the old version and you can measure the difference between those. That’s in fact, something that was mentioned as a best practice in the FDA’s pre-cert working model best practices.

You do have to do periodic filing when there’s lots of changes, but there are lots of opportunities for you to iterate and rapidly release new software in those areas.

Randy:

Hey, Bernhard, what about clinical trials?

Bernhard:

Good question, Randy.

The fact is that only about 10% of the FDA 510(k) clearances involve clinical trials. So the vast majority of medical device filings don’t involve clinical trials, but for the ones that do involve clinical trials, it’s definitely a big barrier to iterating and moving fast.

Clinical trials are an inefficient process. It’s expensive. I think it’s needlessly expensive and needlessly inefficient, but it’s a thorny problem. And it’s definitely not designed for software that can change quickly and forgetting the kind of fast feedback that we have.

The one thing I would say there is that there has been a shift and there has been rethinking around clinical trials, especially during this time of COVID during the pandemic, people have been rethinking clinical trials and actually focusing on how we can be more efficient. And some things that were just not done started to be done more, having more virtual clinical trials that are centrally organized but decentralized in terms of execution in the field, actually having focus on the metrics of efficiency and efficiency of IRB is part of what started happening.

There have been things like adaptive clinical trials that have become more and more prevalent. In 2016, the FDA provided guidance around clinical trials. But obviously there are limits within that as well. There are also some companies that are exploring the concept of a permanent beta and having a continuous IRB process for those types of things.

All of this is still, I would say, a big barrier, but there is movement there and it’s certainly, I think, one of the big areas that we should be focusing on for improving our products and improving how we get life-saving technologies into the hands of patients.

I would also say that if you’re going to be doing a lot of clinical trials, you should really work on optimizing those things. There’s a big advantage in better IRBs, focusing on the metrics, both safety and efficacy metrics, but also efficiency metrics and leveraging things like adaptive trials and real-world evidence.

Randy:

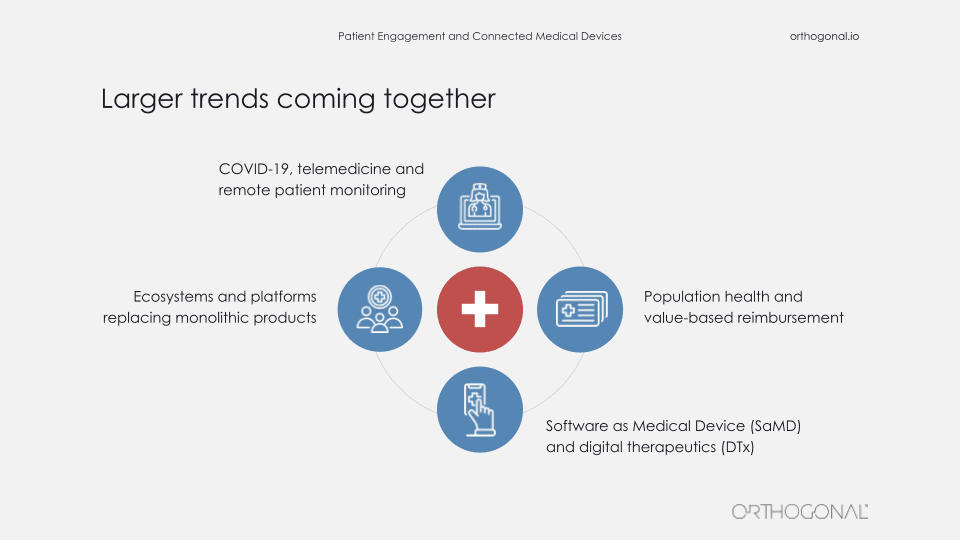

So when we talk about patient engagement and connected medical devices, it’s important to point out that all of this isn’t happening in a vacuum. Now I’m not going to go into these points in a lot of detail, but there are some larger trends going on that you’ll need to keep in mind as you try and crack this nut.

So earlier this month, there was an article written by Erin Brodwin in Stat+ that talked about an important trend with virtual healthcare firms like telemedicine providers and chronic disease management companies. The article talked about how these firms are moving away from the traditional model (well, at least traditional by 2021) of a doctor Zooming with a patient to a team-based care of delivery approach. These are teams of specialists, coaches, and therapists who establish a relationship with each patient and guide them over time. In other words, they’re trying to deliver care delivery models where the patient is actively engaged in the manner that best produces the right outcomes. And this is really an acknowledgment that patient engagement is a team sport. It’s a very sensible model, and we think there’s a lot to it.

The article does give a small shout out to medical devices and acknowledges the role of things like blood pressure cuffs and glucose monitors to provide the clinicians with ongoing patient vitals. But Bernard and I think this is really a pretty enormous understatement of the potential of medical devices to impact patient care and to be a part of a care team for patients.

And instead, we’re going to propose a sort of manifesto here that we would say, “In the future, the connected medical device will be far more than just a tool for clinicians to diagnose, monitor and treat. Instead, the medical device is going to be an essential member of the care team.”

Take the example of a patient who has a respiratory issue, chronic issue and they spend several hours a day doing airway clearance. They’re spending far more time with a nebulizer in their mouth than they are with any clinician that may in fact be their most intimate clinical relationship. And we need to recognize that and take advantage of it.

So the way we’re going to do that is with design thinking, which is really taking off a holistic look at the lives of patients, not just when they use a device, but in their entire lives including their health issues and their care processes, and think about which members of the provider team should engage and when. With this broad view, we can ask questions like:

To get to the point where a medical device is an essential part of a care team, we’re going to have to look at the best roles for medical devices in that team. We’re going to need to remember that in a team, usually team members are not identical and interchangeable. Different people have different strengths and weaknesses, and great teams figure out how to leverage those strengths in a synergistic way.

This is also an important question and an exciting time since medical devices keep getting essentially smaller, cheaper, more powerful, and more connected, so the range of options we have of what a device can do in a care team keep expanding.

Connected medical devices, SaMD, and DTx specifically have certain advantages. First of all, they basically never need to sleep. They can do continuous diagnosis, monitoring, and even therapeutics around the clock using protocols customized to each patient.

The sensors in these devices keep getting smaller and more powerful. So the range of things we’re able to do keeps getting better and better.

And finally, they’re very quantitative and they can take that quantitative data and communicate it. They can communicate it to patients. They can communicate to providers, and they can communicate it to algorithms. All of which give them a very unique vantage point as a member of the care team.

One place where there’s a lot of great design thinking going about the role of algorithms and devices and smart devices on teams of humans is in the U.S. military. At the U.S. Army Research Lab, they believe that the future of warfare will involve teams of people and intelligent agents (i.e., smart algorithms) and smart devices working in concert with people.

Think about what happens when your newest teammate is a chat bot. If you’re on a battlefield and you’ve got a small earpiece, you can talk to a chat bot and it starts acting like Siri in a bad moment where it doesn’t understand you or gives you the wrong directions, what’s the first thing you’re going to do? You’re going to take that earpiece out and you’re going to throw it away because you don’t have time to worry about something else. And there’s hundreds of millions of dollars of research and a huge advantage on the battlefield.

In the same way, we’re going to need to think about how we embed devices intelligently so that they interact well as part of the team?

Devices are not people, but they may be the most undervalued members of your care team. Getting to a place where we can maximize the value of devices is part of that care team, to help with patient engagement, to drive better outcomes.. It’s going to take a lot of hard work, some good thinking, and a very healthy respect for the regulatory process and the things that those regulations are designed to promote. But it is possible. It is doable.

Wrapping up, one of my all-time favorite movies is a documentary called Young At Heart. It’s about a senior citizens’ choir in New England. And what’s unique about this choir is that they sing rock, punk and soul music. It’s really a blast if you haven’t seen it.

What the movie is really about is looking at what gives people their lease on life, what motivates them, and what it shows is that if you’re elderly and your body is just naturally accruing with time different ailments, you need to find ways to motivate yourself and things that are more important to take your mind off the ailments. And in this movie for the choir members, it’s the music, it’s their friendships with each other, it’s the satisfaction of doing a great performance. There’s a really powerful scene in the movie where one of the choir members is seeing the doctor in a hospital and receiving some pretty bad news.

And as the doctor’s delivering this, the only thing the patient really wants to talk about is, “Will I be able to perform next Friday? When can I get back to the choir?” Because that’s what gets them up and going in the morning.

That’s what we need to tap into with medical devices. That’s what we need to tap into with medical devices as part of integrated care teams. Find out what motivates people, figure out what they respond to, fit into their lives and move the needle.

And if we can do that, that’s a pretty powerful reason to get up every morning and fight the good fight. Because everybody we love in our lives is also a patient at some point and will benefit from it.

Thank you.

Question #1:

In your opinion, could some doctors and nurses see this kind of trend as a threat? Are humans going to be switched out for connected devices or robots in this space someday?

Bernard Kappe – Answer:

I think it’s possible. It really depends on how this stuff is presented and how it works. Right? A lot of the stresses, I think, that doctors and nurses have are results of the current business models. I’m married to an anesthesiologist and all of her siblings are in various specialties. And it’s… The pressure to move quickly and to spend less time with patients is really big. And so depending on how you integrate these types of things into what they’re doing, you’ve got to ask, “Does it make their lives easier or do they perceive it as something that improves patient care while not increasing their risk of getting sued or having to do extra documentation?” All these things are big concerns for them right now. I think there are a couple of areas like radiology, where we’ve seen that, where it’s much more directly something that is part of what they do. But I think in that case, the… Again, it’s how you present this. It’s how you provide the education and the feedback that this is something not designed to replace you, because it’s going to be a long time before physicians are replaced… But it’s something that’s going to make you better and more powerful and more effective.

Question #2:

Who is using these techniques in the medical device space?

Bernhard Kappe – Answer:

I think it’s the quote from William Gibson that “The future is already here, but unevenly distributed” is definitely something that makes sense in this industry around digital health. I’d say that the areas that have had the greatest sort of pressure around this have been in areas around chronic diseases, in particular in diabetes. We’ve been doing digital health there for a long time, and we’ve been integrating the ecosystem, and people have been competing and trying to move faster and faster.

So a lot of our clients in the diabetes space are very much using these techniques. They’re doing things like three user Thursdays. They are absolutely thinking about doing things like software segregation, and figuring out how they can apply DevOps and move faster. I’d say cardiac monitoring is another area where some of that is happening. And I think there are a few others… The more connected and the more there are kind of real world pressures bundling and those types of things, the more this is happening. But there are some areas where it’s pretty far behind others, and it’s likely a combination of them… How much is the software part of their DNA and what are the pressures for real-world performance and demonstrating it?

Question #3:

What are the next big trends in digital health and connected devices, from your perspective?

Bernhard Kappe – Answer:

There are obviously things that are ongoing where the regulations are sort of catching up and the standards are catching up, right? So how do we use or apply cloud computing effectively? How do we do that safely? I know we’re working on a consensus report right now at AAMI around that and getting FDA feedback on it. All of the integration of devices outside of the hospital is definitely a trend with COVID that has been accelerated. So telemedicine has gotten a big push and it’s probably not going away. It’s not going to draw back. It’s not going to be all encompassing. So integration of all of these devices. How do you integrate COVID testing, let’s say, or step testing, into telemedicine? How do you integrate cardiac monitoring perhaps with diabetes or with various other things where there are comorbidities? And bring all of these things together.

Those are big trends. And then I think… Another one I think that is really starting to happen is somewhere about two years ago, pharma woke up to the fact that they can’t just do general health and wellness applications. They actually need to have digital health offerings that deal with very specific disease states. So they are building out software as a medical device. New divisions, they are actively building products in this space and putting a lot of money in the space, and you should be seeing a lot more regulatory filings, 510(k)’s coming from pharmaceutical firms as well. So they’re absolutely entering the game and I think it’s going to change a bunch of things in space as well.

Question #4:

A lot of the things that you were speaking about sound great, but I work for a very large medical device firm, and there are a lot of highly established practices that I have to work with. So how do I try to bring about change to happen when I’m just a single player in a very large organization?”

Bernhard Kappe – Answer:

That is a question that I’ve run across before. I think ultimately you have to find the things within that organization where there are both pain points and people… The pain has to be big enough. And there have to be enough sort of like-minded people or people in positions of power who are willing to champion and affect change. So you’re not going to change the entire organization all at once, but you have to look for opportunities within the organization. A lot of the companies we work with either see the opportunity to out-compete folks in this space by applying fast feedback loops and by applying modern techniques, or they realize they’re falling behind in some area and they need to make changes because they’re just not getting products out fast enough. And “Why are our competitors delivering these things into the market and we’re falling behind?”

So if you’re in a company where that’s five years or 10 years away, like I think a lot of the orthopedics companies are, maybe look for another company. That’s one way to do it. Or again, are there change agents? Are there people you can talk to that you can look for in particular areas, where even if you make a small change, that can kind of move the needle a little bit. That’s one way of starting momentum. But it’s a hard problem, right? That’s why a lot of large companies don’t end up being able to last and compete well over the long haul. Because they run into the classic innovator’s dilemma.

Question #5:

If we engage patients through their smartphones, obviously we don’t control what type of smartphone they use, whether it’s Android, iPhone, or a different model or version of an Android or iPhone. How do I handle all of that to ensure a consistently safe and properly functioning experience for the patients within the app?

Bernhard Kappe – Answer:

Yeah, so obviously you can’t test absolutely every single Android smartphone all over the world with all of the OS variants and what specific vendors have put in. So the classic FDA response is to use a risk-based approach to this. And that’s what I would say in this case as well. So for a lot of lower risk things, if the potential harm is really very minor in certain areas, then you can probably test some subset of phones and operating systems as your kind of baseline, and then obviously do monitoring in the field. And you’ve probably got to… Use an app on the phone you’re allowed to, and one that is a… Nope, it won’t work on the phone. We won’t allow you to use this particular smartphone OS variant.

And then if you do run into problems, be able to fix those issues quickly and then add that OS to the ones you’re testing. Obviously do lots of testing automation around this. And then as you kind of move up the risk curve, you can add more testing automation, different environments that you test in. For this, there’s a whole bunch of techniques you can use, from kind of field level self-validation if you’re doing things like Bluetooth testing, and combining that with a whitelist, blacklist, graylist, potentially using device farms and testing automation on those device farms as well, that you can try to apply as you kind of move up to things that are higher and higher risk in terms that… And then the last is basically only allowing certain phone models to be used in the first place. Right? So where do you have to test all of those? But that would be some fairly high risk connected device systems.

Question #6:

Do you think that big tech firms like Google, Microsoft, or Apple, could one day figure this out and become the Google of medical devices per se? And possibly displace the current major medical device firms at the moment?”

Bernhard Kappe – Answer:

So we work with some of those firms. I think it’s very difficult to marry these two different approaches, right? And the different bodies of knowledge. So just as I think medical device firms have challenges around doing modern software development methods and approaches, I think these other companies have difficulties dealing with quality management and with clinical efficacy and all of those types of things. That’s really not so much in their DNA. I think they are starting to work on that. They are catching up on that. And I know they’ve been… We’ve been working with some of those folks. And I think it’ll take a while for them to catch up, but I don’t think that they’re going to be doing everything in this space. Right? There are so many disease states, there are so many things where really specialized knowledge is needed, that I think there are going to be players. Some of them may be ones that grow up outside of traditional medical device companies, or these other companies. And then it’s a question of “Where do they fit in best, who’s going to acquire them ultimately? And will they continue to create value once they’re acquired?”

Yeah. But the jury is still out as to who ultimately is going to win in this space. There’s a lot of white space in between all of these players, and people… Pharma’s trying to figure it out, device companies are trying to figure it out, digital natives are trying to figure it out. And the big tech companies are trying to figure it out as well.

Question #7:

Do you want to make any final on the biggest lessons, any problems or constraints in terms of fast feedback loops?

Bernhard Kappe – Answer:

Yeah. I saw one here as well… So let me answer that, and then there’s another one here as “At the pace the SaMD connected devices, now the medical lifestyles are moving, do you think the regulatory agencies are lagging?” So I’ll take those two.

And so the first one, I think if you think about it, all of this fast feedback loop stuff, right? It’s a technique you can apply to everything as a way of getting information from… More information and acting on it quickly, right? Whether this is you’re doing OODA loops for fighter jets, or you are doing Six Sigma, all of these things are build, measure, learn loops. So if you think about this, it’s just a technique that you can apply to all the constraints that you have. It’s inevitable that it’s all going to get… You’re going to have more data. The regulators are going to have more data, the insurers are going to have more data. Everyone is going to have more data about what’s actually going on.

So not just during your development process, but for things like post-market surveillance, for demonstrating the actual real-world effectiveness, you can’t hide from that long term. You can’t say, “We don’t want to know this stuff. There’s liability there.” People have been able to hide from that, but they can’t really do that anymore. And so you have to think about this thing holistically in terms of post-market and the full lifecycle of the product.

I think the regulators are trying to catch up, and they’re always going to be behind in this space, but they’re actually… For regulators, moving remarkably quickly. Because there is more and more digital health… Software as a medical device, connected device, there are more products that are out there that they are having to deal with. And they’ve hired… FDA has created the new Digital Health Center of Excellence. They are actively producing new guidance around this.

And frankly, a lot of the industry is moving in terms of standards and guidance and things like that. A lot of the things that were involved with, with AAMI, for example… There’s a ton of movement. So it’s never… It’s always going to be a bit behind. And if you’re at the cutting edge, you’re always going to be pioneering some of those things. But I think it’s… It’s not the way it was 10, 20 years ago. They’re moving pretty quickly.

It’s an exciting area. We’ve been doing this for about 10 years now and it just keeps getting faster and faster. And the consumer world and the medical device world are much more rapidly coming together. And opportunities for creating value are huge in space. So… Software is eating the world and it’s eating the medical device space as well.

Thank you. Thanks to Celegence, and thanks to everyone for participating and asking these great questions.

Related Posts

Article

Roundtable Chapter 1 – The One Where the Device Was Only Half the Story

Article

Roundtable Prologue – The One Where the Algorithm Couldn’t Sell Itself

Article

Managing Emerging Risks in SaMD: Strategies for 2025 and Beyond

Article

Emerging Opportunities in SaMD and MedTech for 2025