Article

Roundup: Bluetooth Medical Devices Cleared by FDA in 2023

This blog contains Part 1 of the Orthogonal White Paper titled “Bluetooth for Medical Devices.” The following are links to each part of the white paper:

For more in-depth discussions on Bluetooth from medical device experts, visit our page on our Bluetooth Low Energy for Medical Devices Webinar Series, co-presented by MedSec.

– – –

Bluetooth is an important tool used to make increasingly sophisticated connected medical device systems. For medical device manufacturers and developers to get the most out of the technology, it is critical for them to have a background on what Bluetooth is and what context it works in. In Part 1 of this white paper, we introduce Bluetooth, discuss how it is commonly applied in connected medical device systems, and outline the issues that medical device developers need to address to create a safe and effective Bluetooth-enabled medical device.

Bluetooth is a short-range wireless communication protocol that supports the connection of smartphones, computers and other electronic devices. Since its launch in 1999, it has become the global standard for simple, secure device communication and positioning.[1] Bluetooth technology enables audio streaming and data transfer between paired devices; some of the earliest and most familiar Bluetooth devices are Bluetooth earbuds, headsets and headphones. As a wireless communications protocol, Bluetooth is more secure and requires less battery power than cellular or Wi-Fi connections but has a shorter range and lower bandwidth.

There is no licensing cost to companies developing solutions using the Bluetooth protocol. Rather, the cost of using Bluetooth is made up of the cost of the Bluetooth-enabled hardware device and the time and labor necessary to develop the supporting software.

The Bluetooth standard is continually updated by its steward, an industry consortium called the Bluetooth Special Interest Group (SIG).[2] The most recent flagship Bluetooth version is Bluetooth 5.0, which, according to the 2023 Mobile Overview Report from ScientiaMobile, has penetrated 91% of the combined Android and iOS smartphone markets in the U.S. as of Q1 2023.

Bluetooth is used in the medical device space to communicate between medical device hardware and companion software applications on devices like consumer-level smartphones and tablets, base stations or hubs, as well as devices found in a hospital setting. This arrangement is known as a connected medical device system. Connected medical device systems are used across a wide variety of clinical domains and help improve the functionality and usability of traditional medical device diagnosis, monitoring and treatment. Common applications of Bluetooth in medical devices include continuous glucose monitors (CGMs), pulse oximeters, neurostimulation and heart monitoring.

Bluetooth has facilitated the transfer of device intelligence from the device hardware to the companion software, reducing device production costs and increasing scalability. For example, the addition of AI algorithms within companion software gives connected medical device systems the ability to recommend personalized treatment settings and passively collect and analyze patient data.

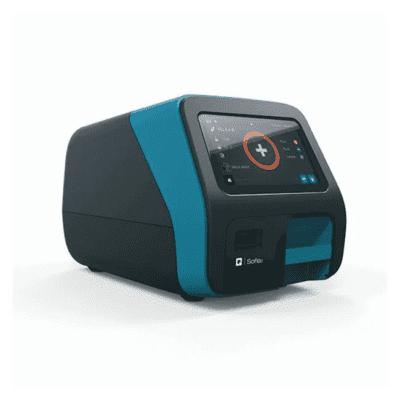

Quidel Sofia 2. Source: Fisher Scientific

The Quidel Sofia 2 is a device used in doctor’s offices, hospitals and clinics to diagnose conditions such as COVID-19 and strep throat. The device’s software analyzes swab samples through a lateral flow assay and provides results within 10 minutes.

Quidel Sofia Q. Source: Quidel

A next generation version of this device, the Quidel Sofia Q, is much smaller, lighter and more accessible. A companion smartphone app controls the physical hardware over a Bluetooth connection. By scanning a barcode on the assay, the companion app can instruct the device on what test to run, capture and analyze the resulting data, and send results both to patients locally and to the cloud.

Nevro Omnia™ Implantable neurostimulator. Source: MedicalExpo

Implantable devices are by nature “headless devices” – they lack a physical user interface, such as a display or touchscreen. Early implantable spinal nerve cord stimulators came with a simple, proprietary external remote control, containing no more than a few buttons and lights. This satisfied patients’ needs at the time but offered only a rudimentary form of personalized care.

St. Jude Medical Proclaim Elite spinal cord stimulation (SCS) system. Source: NeuroNews International

In 2015, St. Jude Medical released a device that offered the rich interface of an iPod Touch to control the implantable spinal nerve cord stimulator. This enabled much finer controls as well as a more detailed user interface. St. Jude supplied users with the iPod Touch – they could not use their own iPods or iPhones to control the device.

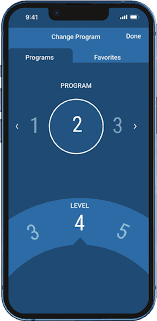

Nevro HFX iQ™. Source: Nevro

A more recent innovation in this category of medical devices comes from Nevro. Nevro’s device uses Bluetooth to communicate between the implanted hardware and the software on a mobile device. However, the software can be installed on a patient’s own personal smartphone. This approach, where the patient selects and provides their own mobile device, is referred to as Bring Your Own Device (BYOD).

Source: Nevro HFX

Nevro’s app improves on the rich control interface with an AI algorithm that analyzes patient data to provide personalized therapy setting recommendations. Patients can use the app to put their implants in and out of MRI Safe Mode, which is an incredibly handy and critical safety feature for Nevro patients.

Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) is a version of Bluetooth that is separate from the original Bluetooth Classic technology. Though they share the same Bluetooth name, they have distinct sets of functionalities. The following table gives a technical summary of the differences between these two technologies:

| Specifications | Bluetooth Low Energy (LE) | Bluetooth Classic |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency Band | 2.4GHz ISM Band (2.402 – 2.480 GHz Utilized) | 2.4GHz ISM Band (2.402 – 2.480 GHz Utilized) |

| Channels | 40 channels with 2 MHz spacing (3 advertising channels/37 data channels) | 79 channels with 1 MHz spacing |

| Channel Usage | Frequency-Hopping Spread Spectrum (FHSS) | Frequency-Hopping Spread Spectrum (FHSS) |

| Modulation | GFSK | GFSK, π/4 DQPSK, 8DPSK |

| Data Rate | LE 2M PHY: 2 Mb/s LE 1M PHY: 1 Mb/s LE Coded PHY (S=2): 500 Kb/s LE Coded PHY (S=8): 125 Kb/s | EDR PHY (8DPSK): 3 Mb/s EDR PHY (π/4 DQPSK): 2 Mb/s BR PHY (GFSK): 1 Mb/s |

| Tx Power* | ≤ 100 mW (+20 dBm) | ≤ 100 mW (+20 dBm) |

| Rx Sensitivity | LE 2M PHY: ≤-70 dBm LE 1M PHY: ≤-70 dBm LE Coded PHY (S=2): ≤-75 dBm LE Coded PHY (S=8): ≤-82 dBm | ≤-70 dBm |

| Data Transports | Asynchronous Connection-oriented Isochronous Connection-oriented Asynchronous Connectionless Synchronous Connectionless Isochronous Connectionless | Asynchronous Connection-oriented Synchronous Connection-oriented |

| Communication Topologies | Point-to-Point (including piconet) Broadcast Mesh | Point-to-Point (including piconet) |

| Positioning Features | Presence: Advertising Direction: Direction Finding (AoA/AoD) Distance: RSSI, HADM HADM (Coming) | None |

With the data from the table, we can observe the following key differences:

For many reasons, including the more efficient power/battery consumption and CPU usage, BLE is the clear choice for connected medical devices.

BLE became standardized with Bluetooth 4.0 release, with all subsequent Bluetooth versions supporting it. This has made it easier for device manufacturers to utilize BLE. Throughout the remainder of this white paper, when we use “Bluetooth,” we are referring to BLE.

Bluetooth Low Energy is constructed using the architectural model of a peripheral device and a central device. The peripheral device is the one that advertises its availability. The central device listens for those advertisements and sends a connection request. Once connected, the central device becomes the “parent” device, and the peripheral device becomes the “child” device.

In most connected medical device systems, the smartphone assumes the role of the central device and the hardware assumes the role of the peripheral device. This works well when both devices are active, but adds complications when the peripheral device wants to talk to the smartphone app while the app is dormant (i.e. running in the background).

Pairing is the process by which two Bluetooth-enabled devices link up together. In the case of BLE, it occurs when the central device’s connection request is accepted by the advertising peripheral device. When two devices are paired, they can start using the Bluetooth connection to send and receive data. Paired devices can store pairing information so that they will automatically establish a connection when they are in close proximity; this is called bonding. There are a variety of methods to pair devices over BLE. Some are more secure than others, and may require extra steps from the user:

Most instances of pairing in connected medical device systems are one-to-one, but BLE is capable of connecting one-to-many (e.g., a mother monitoring multiple children’s insulin pumps on a single smartphone) or many-to-many (e.g., multiple nurses’ smartphones connecting to multiple medical devices around a patient’s hospital bed).

BLE, unlike Bluetooth Classic, does not support the functionality of the peripheral device waking up the central device. Therefore, manufacturers must contend with the differences between foreground and background processing.

An app is considered to be running in the foreground on a mobile device if it is currently visible on the user’s screen. Both Android and iOS prioritize the allocation of the smartphone’s limited processing power for the app in the foreground. When a user is done using that app and moves on without explicitly closing the previous app (i.e., by swiping up on it on an iPhone), it enters the background. Apps idling in the background receive limited processing power. This is not ideal for connected medical device systems that require continuous data refreshes between the physical device hardware and companion software app on the smartphone.

As mentioned above, when an app is in background mode, its companion hardware cannot use BLE to wake it up. Therefore, medical device manufacturers must program scheduled wakeups into the companion app itself to perform any necessary tasks (e.g., a CGM app that wakes itself up every two minutes to retrieve data from the CGM device peripheral).

This strategy, while effective, is not infallible. Background apps have a short window of time in which they can run tasks. Background processing power is allocated to different apps by the smartphone operating system (OS) and has a narrower throughput than in foreground mode. Background processing is also dependent on the device battery. When a device enters Low Power Mode, background app refresh and processing is disabled. Users must manually disable background app refresh through their smart device’s settings.

Even when Bluetooth background mode connectivity works, it is not meant to work for an indefinite period of time. It’s likely that, at some point in the lifetime of the app, something will happen that causes it to no longer work in background mode. This is why user engagement is critical to medical device app development. Developers must give users an incentive to regularly open the app. When user engagement is done right, it has the added benefit of getting information from the patient that may be relevant to therapy/monitoring and that can augment the data gathered from the device. (See Part 4 – Patient Engagement & User Experience for Bluetooth Medical Devices)

Orthogonal has commonly seen Bluetooth Low Energy connections used for the following cases:

Smartphone technology has enabled the evolution of increasingly sophisticated connected medical device systems. Its ubiquity, convenience and familiarity to patients makes it an obvious choice for a connected system. But incorporating a smartphone into a connected medical device system presents additional challenges that are not present when only developing device hardware. This is especially true of devices that run in a Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) environment. BYOD refers to the practice of allowing users to connect their own personal smartphones to Bluetooth medical devices, rather than manufactures supplying users with a dedicated smart device to use exclusively with their medical device. The previously discussed Nevro HFX is an example of a BYOD device.

A medical device manufacturer controls all aspects of their medical device: hardware, firmware and software. They can build a device that is tailor made with the right amount of memory and processing power to give the best treatment.

Smartphones, on the other hand, are consumer devices whose construction and maintenance are overseen by consumer-focused manufacturers like Apple, Samsung, Google and Motorola. These companies primarily focus on developing smartphones that are convenient for consumers, which leads to frequent OS updates and the release of more powerful models.

A connected medical device companion app is just one of the many apps on a user’s smartphone. Despite its critical healthcare functionality, it does not receive priority from the smartphone’s OS.

Due to these factors, using a BYOD smartphone in a connected medical device system means relinquishing a degree of direct control over a significant portion of the device. While this can be a significant drawback, many medical device manufacturers consider it a worthwhile tradeoff to allow their devices to leverage the scalability, familiarity and more powerful processing afforded by smartphones.

Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android are the two main OS for smartphones in the U.S. But there are far more than two kinds of smartphones on the market. The unique combinations of smartphone models with sets of OS versions (e.g. Samsung Galaxy S23 running Android 14), or device profiles, is over 18,000 in North America alone.[3]

This presents a significant challenge to manufacturers attempting to verify a connected medical device system. Connected medical device companion apps need to be verified to ensure they function as intended when installed on a device. But it is impossible to test and verify compatibility for every unique device profile because the time and effort required is far too great. Instead of attempting to test each device profile individually, medical device manufacturers will need to adopt BYOD testing and validation strategies to ensure their app works on a sufficiently representative set of devices. (See Part 5 – Testing Strategies for Bluetooth Medical Devices)

Apple and Google release periodic updates for their iOS and Android systems. These updates go through multiple beta and developer testing periods before they are publicly released. But the rollout and adoption of OS updates are not consistent across all devices. In particular, Android device manufacturers often delay pushing out a new Android OS update from Google so that they can add their own customizations to the Android installation. In addition, when the update does become available to smartphone users, there’s no guarantee they’ll install it immediately. They may delay updating their OS or not upgrade at all because the new OS release doesn’t support their older model smartphone.

Apple enforces a forced upgrade path for iOS, where they highly encourage users to install the new version when it is released, as well as restrict access to specific apps running on older iOS versions. As a result, a majority of iPhone users quickly upgrade to the latest version of iOS.

On the Android side, what OS updates are available to users varies by smartphone vendor and by phone model, and their nudges are far less effective at getting users to upgrade. As a result, there is an increased variance of smartphone OS versions among Android users – numbering in the thousands of versions for Android versus dozens of versions for iOS.

Both Google and Apple allow application developers and publishers to set a minimum OS version required on the phone before allowing the download of an app in their respective app stores. To access the application, users must update their phones to a newer version. Because of the aforementioned lag in Android OS update adoption, there is a need to cover far more older Android versions for a longer period than iOS.

In addition, new iOS and Android releases can introduce new bugs that negatively impact the performance of connected medical device systems. In a worst-case scenario, updates can break essential features of a medical device system and require an emergency patch. Medical device developers need to closely monitor all upcoming updates for both operating systems, and test accordingly.

The combination of Bluetooth connectivity and smartphone ubiquity has greatly expanded the access, ease of use and capability of medical devices, especially those that patients use in their daily lives. This combination enables the increasing sophistication and power of connected medical device systems that can have a truly positive impact on patients’ health.

However, Bluetooth is not a perfect technology and requires workarounds and mitigations to maximize its potential in medical devices. Next, we’ll delve into the challenges and issues of using Bluetooth in a connected medical device, as well as recommend best practices for taking on those issues.

– – –

This blog contains Part 1 of the Orthogonal White Paper titled “Bluetooth for Medical Devices.” The following are links to each part of the white paper:

1. https://www.bluetooth.com/learn-about-bluetooth/tech-overview/

2. https://www.bluetooth.com/about-us/

3. Source: ScientiaMobile

Related Posts

Article

Roundup: Bluetooth Medical Devices Cleared by FDA in 2023

Article

Testing Strategies for Bluetooth Medical Devices

Article

Patient Engagement & UX for Bluetooth Medical Devices

Article

Cybersecurity for Bluetooth Medical Devices