Article

How nen DTx Will Help Kids with Cancer to Manage Pain

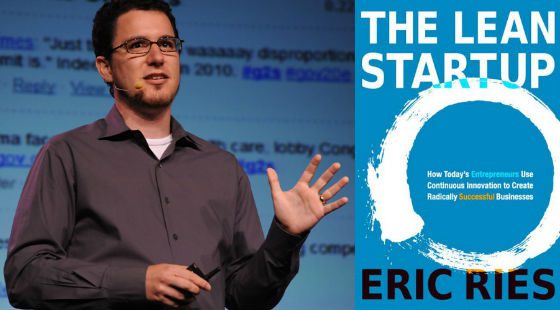

It’s been 10 years since The Lean Startup was published by Eric Ries, an American entrepreneur and creator of the methodology of the same name. The New York Times bestseller has certainly become a core text for many entrepreneurs and is part of standard operating practices for organizations of all types ranging from startups to large enterprises to government agencies and nonprofits.

For the uninitiated, Lean Startup is a business strategy and method for developing and launching new products through a combination of hypothesis-driven experimentation, frequent iterative product releases and validated learning.

Orthogonal has been a major proponent of the Lean Startup approach since its inception. It has proven repeatedly to us to be the one of the best ways we know to build successful new products and businesses, including Software as a Medical Device (SaMD), digital therapeutics (DTx) and connected medical devices.

Hosted by Orthogonal’s CEO, Bernhard Kappe during a Chicago Lean Startup Circle event on September 22, 2011, below is a full transcript of the Actors Studio-style conversation with Eric Ries during his book tour visit to Chicago to promote the release of his book This event was attended by a packed auditorium of hundreds at Northwestern University’s Thorne Auditorium.

You can watch the conversation here, or read the transcript of this conversation by scrolling down.

Bernhard Kappe: Eric Ries had come to Chicago for about a year now and the stars had not aligned until today. So, I’m very happy to have Eric here.

I actually was first exposed to customer development and to the Lean Startup approach when I saw his blog. And at the time I was really searching for better ways of helping our customers. We helped companies build software products. We launched a lot of products for them.

And you can build the greatest product. You can have the greatest user experiences on it, the greatest developers, the greatest software development process but that’s not a guarantee for success. In fact, it’s only half the battle.

You need to actually work on the other side of things. You need to think about your customers and validate your hypotheses on that side and lo and behold, the Lean Startup approach came and I said, “This is great. This is what our customers need. This is what the companies that I mentor need. Everyone needs this.”

So, I joined the Chicago Lean Startup Circle and I ended up taking on organizing this group and getting deeper into the method. And so Eric has been a great inspiration to me and to a lot of folks here. I know a lot of companies have gotten a lot of traction out of this approach and Eric’s been working very hard on a book over the last six to nine months, a year or so and finally published it and is kind enough to come here and have a conversation with us about it. Those of you who have read the book yet, a lot of them have it now. It is really awesome. Actually, it really helps you kind of think through the problems and not just sort of all cookie-cutter recipes but really figure out how to get the most out of it yourself and think through it. So, ladies and gentlemen, Eric Ries.

Eric Ries: Wow! Hi. It’s an incredible turnout.

Bernhard Kappe: Yeah. It’s pretty good.

Eric Ries: You guys feel like you must do these events all the time. Thanks for surviving the line of death, everybody. Much appreciated.

Now, supposedly, hopefully, we are live streaming tonight and the people who were upset that they couldn’t have their city on the book tour, my publisher goes onto the … I insisted my publisher do the book tour metrics-driven, which I think may have been a first for them. And so, I went onto the meetup.com site to see where the biggest of these sort of Meetups were. Chicago, number three, number four.

Bernhard Kappe: Number four.

Eric Ries: Number four. Boston, look out, because the energy here is amazing. And so, you guys are lucky enough to have a thriving community, so it made sense to come here. A lot of people couldn’t go to their city. So, there are people gathered as we speak for the simulcast. So, if everybody can’t be here with us, but is here virtually, I just want to say welcome. People can ask questions?

Bernhard Kappe: Yeah. So, we have the hashtag #LeanStartup

Eric Ries: Yeah. So, tweet your question to #LeanStartup and say where you’re from and we will try to answer some questions from the virtual book tour. So, thank you all.

Bernhard Kappe: Cool. Welcome to Chicago.

Eric Ries: It’s great to be here.

Bernhard Kappe: So, how did this all come about? How did you first get into this?

Eric Ries: Yeah. Let me tell you the master plan that I anticipated the future of great acuity and knew that this is going to happen, because you have to understand, I grew up programming computers, so that’s actually a job I really understood really well and I was pretty good at. And I was pretty sure I was going to program computers for the rest of my life. And if things had gone a slightly different way, if any of the early companies I had helped to build had any customers whatsoever, it might have continued that way. But unfortunately, I kept building products that no one’s using today that today are still as technically brilliant as they ever were, the most amazing cutting-edge stuff that no one at all is using.

And so, by the time I got to IMVU, these stories were in the book. The last company I started in 2004 called IMVU. And we did things really different because my co-founders and I were really sick and tired of doing the same old thing, being told that we were geniuses, even as we were driving our company off a cliff. And then we’re like, “How can that be a genius way of building a company if we keep embarrassing ourselves so publicly?” Luckily, we had Steve Blank as an investor and on our board and he encouraged us to think differently.

And we didn’t want to just make the same mistakes over again. So, we did things really radically different at IMVU. Most of you will know the story. Some of you, this is new. And so, for those who are new, for example, we do stuff like continuous deployment, which is the process of putting software into production 50 times a day on average. And I always take a look around, see if there’s an engineer hearing that the first time slowly shaking their head, being like, “That does not seem like a good idea.” We’ll get to that.

And IMVU was a very successful company and I’m very proud of what we accomplished there. And in Silicon Valley, it’s an echo chamber. So, if you have even the tiniest iota of success, you immediately go on the advisor circuit, asked to advise other companies about what you’re so good at and work with VCs and spread your knowledge. And I had really no experience with that, but people would ask me to come in and they say, “Oh, we’re having these kinds of problems. What do you think we should do?” And I say, “Well, I won’t tell you what to do, but here’s what we did at IMVU,” and I tell them the story about, “Hey, we did this thing called continuous deployment and obviously get fast iteration.” And the universal response was, “That will never work.” And it’s like, “That’s odd.”

I’m not discussing a hypothetical thing that might work. I’m just telling a story. I was there. I saw in my lines people say, “I’ll never work for a team larger than 5x.” I’m like, “We’re already at size 5x.” So, I took logic a long time ago in college and I recall and people just look at me like I was completely crazy and they would want to argue with me about is what I’m saying true or not and could it possibly work?

And eventually I go, “Listen. You called me.” So, I’m on vacation. “This is my break.” I tell them, “Don’t do it. Hey, man. It’s your company.” And here’s my brilliant plan. My brilliant plan was to keep having it over and over again and I thought, “All right.” To Steve I said, “I’ll start a blog.” And here was my genius plan for the blog. I would put some of these stories on a blog and then if people want to talk to me, I say, “Before you call, look at the blog. If you think it’s crazy, don’t call me.”

I was so embarrassed. This is 2008 now, and at that time, there were not a lot of entrepreneurship blogs. People were not writing. I mean, it was not considered cool. In Silicon Valley, there were very few people doing this. So, I was really embarrassed. It was kind of a deviation from the path I was on. So, I didn’t even put my name on the blog. It just said, “Lessons learned.” Didn’t say anything to anybody. I used the bloggers default template. No design, no nothing. And I said to myself, “Well, if the lack of design ever gets in the way of a successful blog, I’ll change it.”

And all of a sudden, people started reading it and sending me questions like, “What is your network for your 3D avatar business but how do I know it’ll work for my business?” I once got one that said, “Sure, it works for 3D avatars, but not for my 2D avatars.” But several people were looking for my software. And I knew Steve and I know we’ve done some work together and I actually audited his class at Berkeley right when he was first teaching this thing called customer development, and he’s in enterprise software. And people would take his class and go, “Well, sure. It works in enterprise software, but how will I know it works in consumer internet?”

If you think about it, that sort of advice is so irritating because of all the advice on the forum, I did X. Then, I got really rich. So, if you do X. You also get really rich. And again, those of you who took logic sometime in the distant path will go, “That’s not a valid syllogism.” How do I know you really did that? How do I know X caused you to get rich? How do I know that you’re really rich? How do I know that you got rich because of evidence in spike doing X, how do I know what worked before will work now. How do I know it worked in your industry?”

I mean, think about all the problems that every single startup advice, every story, every move, it’s all the same. And I was on the receiving end of those questions and I was determined to try to give people an honest answer. And the only way I knew how was to try to develop principles that explain why the crazy tactics we had done in IMVU and continuous deployment worked. And in the process of doing that, we needed terminology for it and I was studying … The thing that helped me the most as an entrepreneur was studying lean manufacturing. And the break from realization for me was, “Oh, if we change the definition of progress from making high quality stuff, as it is in manufacturing, to what we now call validated learning about our business,” we can still use all the techniques from lean manufacturing and that means that we were drawing this huge depth of knowledge and wisdom that can help us get a head start in our movement. So, I called it Lean Startup.

It is actually the three-year anniversary this month of me having the courage to say that out loud in public, because it was so … Thank you. I feel like it’s a lot of anniversaries. It’s been one year since Bernhard started the Lean Startup Circle here. It’s actually my birthday tonight, so we have a lot of things for the anniversary of, and so, yeah, my three-year blogiversary also.

That’s how it started and pretty quickly, it took over my life. So, my plan was not to become a professional expert. What is that anyway? What kind of job is that to have? I don’t know. Peter Drucker famously said that people called him a guru because they couldn’t spell charlatan. I totally feel that way.

So, I do this for a living now and it’s just, I feel very honored to share tonight with you guys. I feel like, every day, I get to take credit for your work, which is awesome because I don’t do what you guys do. You guys are the ones on the cutting edge of what really is working and not working and the people who build these Meetups are now in more than a hundred cities around the world, are the people who actually are seriously everyday advancing the state of our entrepreneurship and I think we’re on the brink of something really big. So, I’m very honored to be here with you all. It’s been a very special night for me.

Bernhard Kappe: So, the term lean startup confuses a lot of people outside of the lean startup movement. A lot of people think it’s bootstrapped in a garage or in someone’s basement, but that’s not really what you mean by lean startup. You mentioned you’re from lean manufacturing.

Eric Ries: Absolutely.

Bernhard Kappe: But you also have a somewhat different idea of what a startup is. So, can you talk a little bit more about that?

Eric Ries: Sure can. One of my favorite topics. First of all, just so everybody knows, here are the most common misconceptions about lean startup. Who here is new to lean startup tonight? This is your first event that you … Okay. All right. Good.

First of all, keep your hands up for just one more second. Everybody else, if you’re sitting next to somebody who’s got their hand up right now, if you wouldn’t mind indoctrinating them to the movement as soon as we’re done here, I’d appreciate it. Introduce yourself and see if you can help them.

People who are educated about this as history will understand what lean manufacturing is, but people who are … Lots of entrepreneurs, especially in Silicon Valley, they live in their own special little bubble. The people who never studied anything. It’s like, “Oh, I have had an idea today. It’s the first time anyone ever had that idea.”

So, here. It is not about being cheap. It’s about learning to use capital well. It’s not about taking VC or not taking VC. Again, it’s about using VC when it’s appropriate tactically. It’s therefore not about bootstrapping and it’s not about replacing vision with data, even though we’re very data driven and we’ll talk more about that.

So, I guess if I start off the story about how this began, so that was three years ago. I’ll just continue the story a little bit. It will answer your question. I was invited to the Web 2.0 Expo in the spring of 2009, so about six months later there was already enough following that they wanted me to give a talk at Web 2.0 Expo.

Now was going to be the first time, not only was I going to say some of these nutty things out loud, but now in public in front of an audience. And I believed that the goal at that time, the way I thought about what we were trying to do with lean startup was to put the practice of entrepreneurship on a more rigorous footing. So, we weren’t using the stories you read in the press and movies as our text quote for what entrepreneurship is but we can do something a little bit more rigorous.

So, I was like, “Oh, we should begin with a definition of what is a startup.” So, I got up on the stage and I had a slide that said, “A startup is a human institution designed to create something new under conditions of extreme uncertainty.” And that’s still what I believe a startup is. And I noticed something as I was writing about that topic that it doesn’t actually say anything about how big your company is. It doesn’t say anything about what industry you work in or what sector of the economy. It just says you’re trying to do institution building under conditions of extreme uncertainty.

So, I said, because I was on stage as confidently as I could muster, “These principles should work in any size company, four to 500, garage, government, non-profit, shouldn’t matter at all.” And I had no idea what I was talking about. I want to be really clear. It was a logical deduction from first principles. I felt like one of those scientists that make those wacky predictions and people are like, “What? Are you sure?” I’m just telling you what the theory predicts.

And from the very first time, literally that day, I was mobbed with people who, if I would met them on the street, any other time, I would have been like, “You’re not an entrepreneur. You’re some boring, big company bureaucrat.” But then, when I talked to them, they all dressed well, they go to a regular office with good benefits. They don’t eat ramen noodles. You wouldn’t make a movie about them as entrepreneurs. They’re just regular corporate dudes.

And then, we started to talk and they’d be like, “I had this vision for how my company needs to adapt or die,” and they start to talk to me about what they’re doing. It’s like, “Wow! This is a very visionary person.” And they would want my advice and I’d try to talk them out of it. I was like, “Listen. First of all, I don’t know anything about being inside of the company. I hear there’s a lot of politics and you’ve got to learn and I can’t help you with that.” And they’re like, “Did I mention I’m a general manager of this company? I got the politics handled. Obviously, I would have been fired years ago if I wasn’t acing it.” I go, “Okay. Well, that’s cool then. Let me tell you about the future of the internet, these new open source, highly leveraged product development ideas.” And they’re like, “Yeah. Duh. I know. The Internet’s going to change my business. We have to adapt or die.” It’s like, “Okay.”

Well, I read this great book called “The Innovator’s Dilemma” and it lays out some things you need to do, kind of entrepreneur prerequisites. You got to make them a separate division and separate P&L. And they would be like, “Yeah. I read the same book, too. And guess what. What did I just tell you? I’m a manager of an autonomous division with our own P&L. We’ve got this innovation black box.”

And, finally, I was like, “Yeah. I guess you’re supposed to listen to customers,” and ask them, “This conversation isn’t going very well. Why do you want to talk to me?” And they said something very similar, each one. It was basically like, “We built this black box of innovation just like Clay Christensen said.” And what are those people supposed to do every day, because in the book, it’s just like, “Set this structure up and innovation will happen.” In the book, I got this metaphor. It’s like, I got the kindling and the wood and the matches and all these ingredients sitting here and it’s like, “Where’s my fire? It’s not happening.” And implicit in the question was so clear that these were people who had promised some CFO somewhere that their innovation was going to pay off. And now it’s like, six months in, and they got nothing to show for it.

As entrepreneurs, we’re used to having nothing to show for it. We live like that, but if you’re a general manager who made a plan and now you’re not hitting the plan, and I try to give him the best answer I could, which is like, “Well, if I was in your shoes and if I was doing a startup, here’s how we would think about it,” and that began the process of realization for me that took a while to figure out, but basically the word entrepreneur is now a career. It’s a job title you can have. It’s a thing you can study and practice and get good at and doesn’t matter what kind of industry you’re in. That’s totally irrelevant. And therefore, we have a lot to learn from each other. There’s always entrepreneurs advancing the state of the art, all these different kinds of companies and we could all work together to figure out, “Hey, how can we help each other? What can we do?” And that is a big theme in the book, wanting to reach people who wouldn’t necessarily even think of themselves as entrepreneurs.

I’m certainly convinced that for corporate CFOs and executive managers, there should be people who work for your company that have a job with business cards that says, “Entrepreneur” on it. And people who specialize in that. So, we don’t have to be confused about what kind of management we are doing, when we’re in this brand new, highly uncertain situation. We’re doing entrepreneurial management, just a different kind of management than what we learned in the 20th century.

Bernhard Kappe: So, the thing that management can learn fairly early on is you cannot manage what you can’t measure. So, and typically in a large company, you have P&Ls, you have plans, all these ways of forecasting, of measuring. But in a startup, as you said, you may not have anything to show for it in six months or longer. So, you mentioned you’re supposed to have a different way of accounting for that innovation count. Can you talk about that a little bit?

Eric Ries: Sure. Let me give a disclaimer first. Some of you came to a talk you thought was going to be cool and exciting, it was going to be about entrepreneurship. That’s the sexiest topic alive right now. And now, so far, all we talked about is management. And now, we’re about to talk about accounting. What could possibly be more boring? Accounting is one of those words you use to put people to sleep. And I apologize. That’s what you’re in for, so you can leave anytime. The doors are unlocked.

I actually think entrepreneurship is too cool right now and it needs to get a lot more boring, because it’s all these movies, everyone’s excited about entrepreneurship. And look, I think there’s an amazing thing happening there. There’s this worldwide entrepreneur so many of you are a part of is super exciting, but the actual work of entrepreneurship is unbelievably boring and excruciatingly difficult and often embarrassing and humiliating. It’s not exactly cool. So, actually, we’re going to make entrepreneurship better, we have to make it really boring, make it a topic that we study and therefore can improve.

Let me just give a quick history lesson, with all those anniversaries. This year, 2011, is the one hundredth anniversary of the idea of management. The very first management book is called The Principles of Scientific Management. It was written by Frederick Winslow Taylor and it was published in 1911. So, management has had a pretty good run in these past hundred years. And if you think about what we have accomplished in general management in the 20th century, it is all about planning and forecasting.

When I was doing the research for the book, I had a really shocking discovery when I was reading about the original general managers, the people that worked out how to build a multidivisional company, the kind that we now take for granted. People like Alfred P. Sloan and General Motors. And they figured out that, by using what we now call accounting, they could make forecasts that they can use to hold managers accountable.

So, everyone knows that, if you’re a manager, your job is to beat the plan. Everyone will say, “You beat the plan, you get promoted. If you are slightly below plan, you get fired.” That’s the basic rule of management today. And here’s the thing that really freaked me out. I mean, I almost fell out of my chair. I realized, “Oh, my god. There was a time when people made forecasts of things and then had them. I’ve never seen that before. I had never in my entire career ever seen a forecast of anything that turned out even remotely accurate, because I thought planning forecasting was a kabuki dance that we did in order to raise money from VCs. It was like the way you kind of were used to, instead of showing everyone that you stabbed yourself with a knife.” I feel like I can do this in a painful way that proves how serious I am. I honestly didn’t know what it was for because we never looked at those plans after we’d written them. We just put them in a … That was it. We just used it to bamboozle the investors. I go, “Why do we do that? There must be a good reason.”

Well, it turns out, if you have a long and stable operating history for your business, then you can predict what’s going to happen with some regularity and that’s still true in a lot of businesses and a lot of parts of companies. If you run a search engine business, you can tell me that the top weeks and months for a search engine query are you can tell me, “Yeah. When it’s the Super Bowl, a lot of people search for sports things.” You know that stuff and therefore, you can make a plan.

And the reason that’s so important, I want to emphasize this, because, let’s say I’m the general manager in charge of sports-related searches at my search engine company. And I happen to launch a new feature the day before the Super Bowl, and then the next day, everything’s up and to the right, a huge surge of new sports queries. Can you imagine managers like, “I should be promoted, I did such a good job.” You’re like, “No, you didn’t, because we have 10 years of historical data that shows that would have happened anyway. Doesn’t count. You’re fired.” The general managers know not to do that.

Now, a show of hands, who feels like the world is getting more and more stable every day? Good question. So, all of a sudden, all of us, entrepreneurs and managers alike, are finding ourselves in a situation where there’s more and more uncertainty and less and less stability. And that means our basic management tools don’t function anymore, because we can’t make plans and forecasts. That’s why a business plan in a startup is such a waste of time because they’re not incoherent. They’re just based on raw facts because there’s no operating history with which to make a projection.

So, as entrepreneurs, we can speak frankly, right? We’re candid with each other here? We like to make fun of big company people and corporate CFOs and VCs, because they’re so conservative. They don’t know. They don’t think business plans work. They focus on ROI and bottom line. How stupid is that? But I’m actually kind of sympathetic to their problems because let’s go back to that corporate manager who comes back a year later.

So, let’s think about what happened here. And this will sound familiar to anyone who’s ever negotiated with their CFO as well as anyone who’s ever negotiated with a VC and maybe some of you ever had this negotiation with your spouse. Doesn’t matter who your stakeholder is. At time zero, you said, “Listen, I got this great idea and this amazing plan and if you give me a year and a million dollars and a team of five,” or whatever the resources were, “I’m going to promise you the sun and the moon and the stars. It’s going to be amazing. We’re going to make zillions of customers. It’ll be just like that movie, The Social Network. Just all that.”

A year passes. What do we know for sure? We know for sure that the money got spent. Entrepreneurs always successfully spend the money as planned. We know that people were busy that whole time. We probably know that product milestones of various kinds came and went, products made. And look, let’s be honest. The Social Network thing didn’t happen. I joke, when I first started, I was actually in a dorm and I had the first half of The Social Network experience. It’s a really difficult, hard work part, but it’s necessarily the fun part where you get to sue each other and make a lot of money.

So, I’m a corporate CFO for the spouse and it’s like, “Okay. Well, that sounds like a giant failure.” And the other person’s like, “No, no. But, listen. We’ve learned so much. If you just give us another year and $2 million, we’re totally going to nail this and go nuts because we’re halfway through. We did the first half and we did the second half.” Can you feel the sympathy for that stakeholder even if that has been you and your career? How do you know if they actually are on the brink of success or they spent the last year goofing off? How do you know? In both cases, the gross metrics, what we call the vanity metrics are exactly the same, pathetically small revenue compared to plan, pathetically small customers compared to plan.

And just think about this a second. Our current accounting methods are so bad, they cannot tell the difference between a team that is on the brink of a breakthrough success and a team that spent the year goofing off and doing nothing. We’re not talking about a three degrees difference in performance. We’re saying, “Best team ever, worst team ever.” I don’t know. I talk about the failure of the paradigm. That is the failure of our current management paradigm, cannot differentiate.

So, I try to make the case over a huge chunk of the book is making the case for something I call innovation accounting, not to be confused with innovative accounting to read chapter carefully, which is a mechanism for evaluating whether an innovation team is actually making progress objectively so that we can actually, we can start to make predictions about all the operating success, are we getting closer to product market fit or do we need to pivot? And through that framework, I believe we can basically develop a new accounting net for our new management discipline that will be a lot less BS and a lot more, not the vanity metrics, but really about who’s really learning what customers want and who’s really making progress.

Bernhard Kappe: One question I have: “Did you in that first startup get to jump from a roof into the swimming pool?”

Eric Ries: No. We were in New Haven, Connecticut, where it’s always too cold for that, but we did a lot of really stupid things and we thought for sure it was going to work. We were a hundred percent convinced. And I’ll tell you the most painful part. In the movies, everyone the protagonist talks to says it’s a bad idea. They tell them not to do it. They’re all the cynics and the skeptics and they’re always like, “No.” And the protagonist is like, “You old man. You don’t know. I see the future. You’re mired in the past and I’m going to show you one day.”

If you ever had this experience, you’ll know. The most painful part, the most humiliating part is having to go back to those people and be like, “You were right. It didn’t work out. I would have been way better off going into banking or something. Good. Thanks for that advice. You were right.” Because in the movie, it never happens that way. Those people are never right, but in real life, the cynics are right most often. If you want to be right, being cynical is a very good way to be right. You’ll be right all the time because most things don’t work. And so, on purpose, we ask ourselves, “Do we want to be right or do we want to change the world?”

Bernhard Kappe: So, I mean, almost all entrepreneurs started with a vision and they want to make that vision a reality, but you can plan it out or you can just go build it. Those are kind of two typical ways the folks do it, but most of those resulted in failure, 10 startups or something like that.

Eric Ries: It’s horrendous. Yeah.

Bernhard Kappe: It’s hell. So, what do you do instead?

Eric Ries: So, imagine I was a scientist and I’m trying to learn something about the structure of some chemical and there’s only two options. My options are, I spent all my time at the whiteboard thinking my way through the answer to understand how this works or the other option is I run into my lab and just throw all these chemicals around and see what happens. You’d be like, “Dude. In the one case, you’re going to accomplish nothing because you’re just going to be theorizing about something you don’t know. The second case, you’re probably going to die with all the chemistry here.”

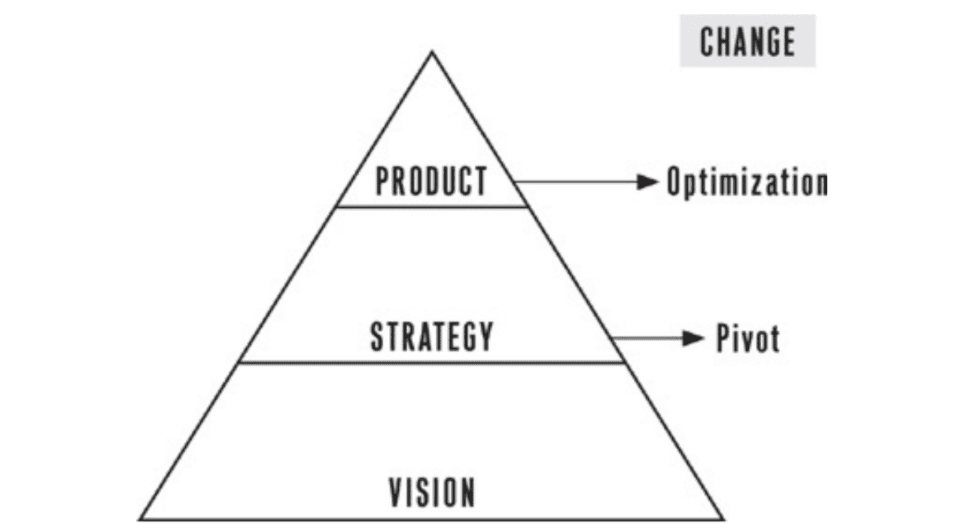

Neither of those is science. Science is we have a theory, we make a prediction, and then we test that prediction empirically and whether we succeed or fail with the experiment, we learn and the learning is what’s valuable. That’s what we want to do. We want to have a scientific approach to entrepreneurship and the theory is the vision. The experiment is the strategy and the specific thing we do is we build a product.

So, in the book, there’s a little pyramid. Vision is the foundation, strategy is the middle layer, and product is the tip. When we changed the product, we’re just doing optimization. When we add a feature to a product, make it easier to use, we assume that what we’re building actually somebody cares and it’s the right thing. And I had a really embarrassing experience. If you have a product that people don’t actually want, making it easier to use just helps them realize that they don’t want it. In fact, it’s really confusing and that’s what happens in optimization. If you’re on the wrong track, getting there more efficiently is, you’re in trouble. And that’s why we say, “Don’t focus on optimization. Focus on learning and if you’re learning, then you want to pivot.”

And I apologize. Pivot is probably the most overused buzzword in the last year. Sorry about that. But that’s what it is. It’s the most important concept in entrepreneurship, bar none. A pivot is a change in strategy without a change in vision.

So, if I had a theory I’m trying to understand, I realize I feel like it is relatively my theory. I want to prove that it’s right and I conduct an experiment, which I was like, “Nope. Not correct.” If I’m a scientist, I don’t give up and go, “Oh, this is so relative,” because why starting to work out? And that wasn’t very good, but I also go like, “No. I’m going to run the experiment again and again and again, and eventually, it’s going to prove a different result.” Both of those things would be crazy. And that’s the one thing is I run this experiment and it’s not going to … Basically, nothing’s happening. Something’s supposed to happen. So, I’m going to work on making it more efficient to run that experiment faster, or make less successes so I can keep running. It’s like, “What’s wrong with you?” No. Find a different experiment that can help you validate or invalidate your vision. That’s what we’re talking about. So, we don’t want to be stubborn, so we put the plane straight into the ground. We want to do this systematic thing, pivot to something different.

And that’s why I say a startup is an experiment, not an experiment in can something be built, because guess what. We live in a time now where we can build anything we can imagine. So, our question for our time is not can it be built but should it be built? And if that’s a really different place to be in historically. If Fred Taylor was here from a hundred years ago and we said, “Hey, think about what you should build.” Be like, “We know what needs to be built.” We need stuff, lots and lots of stuff to clothe, house, and feed people. And we have more stuff than we know what to do with. And so, that would be a really different conversation. He would find what we’re dealing with kind of strange. But he certainly wouldn’t have recommended we take a non-scientific approach to it. And so, that’s what we’re trying, to get out of the sort of alchemy and into the sort of science.

Bernhard Kappe: So, there’s a bunch of hypotheses that they have and if I recognize in the beginning that they are hypotheses because, as you said, it’s going to be uncertain. There’s a whole bunch of things that you don’t know because you have a hypothesis on. What are the most important hypotheses to test first?

Eric Ries: I am going to answer this question, but this is a disclaimer. Warning, this may be hazardous to your health. If you happen to be an MBA, you will be especially prone to this problem we call analysis paralysis. Some people like analyzing their idea to death and forming the hypothesis and writing them down and … I used to do a ton of iterating and pivoting at the whiteboard. I keep rearranging my business model to make it more and more efficient but there’s no facts. Just me at the whiteboard, so just not his account.

But if you can get over that, it helps to know what we are trying to test. And so, in the book, I talk about two what I call leap-of-faith assumptions. And we call them leap-of-faith assumptions because if they’re wrong, you got no business.

So, whoever builds a business plan? Just a show of hands. It’s okay. Yeah. Keep your hand up if there was a spreadsheet in the back of the business plan. Okay. Keep your hand up if the spreadsheet makes predictions of revenue in year five. Keep your hand up if there’s a revenue in year five that will be at least $100 million. That’s not bad. It’s Silicon Valley, by the way. Everyone’s hand is up.

Bernhard Kappe: Was it your actual work or was it rejected?

Eric Ries: Yeah, yeah. Show me if you actually made a hundred million dollars in year five. Show that value and his hand goes down. We’re really good at making plans but not necessarily making any money.

Now, if I had one of your spreadsheets with me, I know exactly what it would be. It’d be in five point font in appendix C and I search in there and I look and I say, “Look. Here’s a box that says, ‘10%.’ I wonder what that is.” I trace my finger over my magnifying glass. It says, “Percentage of customers who sign up for the free trial.” Hmm.

Now, why is that in the five point font in appendix C? That should be in a giant banner in red font on your wall. That’s what I call a leap-of-faith assumption. You know it’s a leap-of-faith assumption because if I change that 10 to a zero, what happens to your brilliant five-year revenue projection? Your whole spreadsheet goes to zero. So, it’s pretty important. So, the two most important leap-of-faith assumptions are what I call the value hypothesis and the growth hypothesis. The value hypothesis says, “How do we know when a customer’s used this product, they experience value? And then how does this become value creating rather than value destroying business?” If all you want is growth, just do a Ponzi scheme. Seriously. So fast. It’s awesome. A lot of companies are actually Ponzi scheme. They just raise more money in order to raise more money and on a unit basis, they’re actually destroying value. And the rule one of capitalism is that when people voluntarily exchange value, more value is created. And so fraudulent activity doesn’t pass this test and a lot of startups are inadvertently violating rule number one of capitalism.

Question two is assuming that you’re creating value to people, how will a business grow? Most entrepreneurs think that growth just happens by magic but it doesn’t. Growth is a very specific mechanism. And in the book, I lay out what I call the three engines of growth, which are these feedback loops that cause sustainable growth rather than just your one time like, “Oh, I had tech crunch. Hooray!” Sustainable growth means new customers come from the action of past customers. That’s it. And that can happen because past customers refer to new customers. It could be because the past customers come back within a sticky or an engagement-type business. Or it could be that the revenue we generate from past customers, we reinvest into acquiring new customers. So, those are the three key engines of growth. You have a kind of feedback loop that we can quantify.

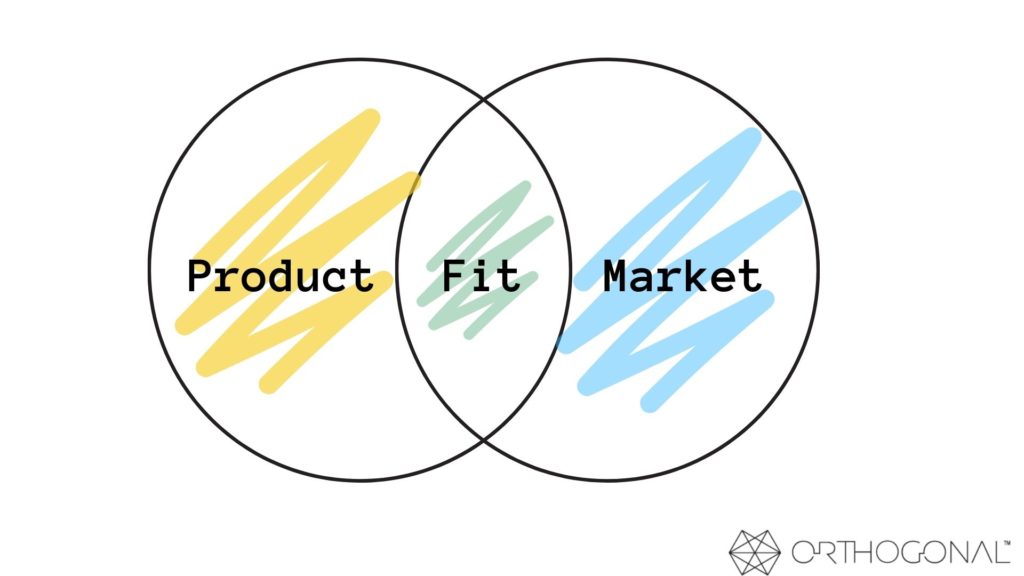

If we can get both of those two things working simultaneously, a product that creates value for customers and creates sustainable growth, I believe that is the definition of product-market fit. And the only question is how fast will it grow and how much money we’ll make and that’s what the innovation accounting framework is designed to help us figure out.

So, don’t think about it too much. This is actually not that complicated. Don’t go read a textbook on business strategy. Just try to make a quick guess about which engine of growth and how will you know that it creates value and then give yourself a hard deadline to build what we call the minimum viable product, which is what is the least amount of work we have to do to establish real baseline data about those leap-of-faith assumptions? Like going back to my 10% signup rate example. If that number is really zero right now, wouldn’t you want to know? Isn’t it better to have bad news that’s true than good news that you just made up?

And yet, that’s what most of us are operating on, the good news that we made up. We’re like, “Wow! We can’t believe the good news. So good.” Or we follow the plan and ship it and see what happens, which is a problem because then you’re guaranteed to succeed in seeing what happens. Something will definitely happen, guaranteed. But that isn’t enough.

So, if you can’t fail, you can’t learn. So, we want to make predictions about what those numbers are supposed to be and then in microscale, get the real data about where we are right now and then we can try to tune that engine to make the number go from zero it is today to the 10% it’s supposed to be. And then, that gives us a framework for deciding if it’s time to pivot because, in my experience, if you’re using real actionable metrics, not the vanity metrics, if you’re looking at these inputs, the number starts out at zero and then maybe it’ll go like 0%, 3%, 5%, 7% over four or five months. You be like, “We’re at 10% there. We’re going to make it. We can pretty much see the trend.”

And then, I meet teams that go like this. It’s like 0%, 3%, three-and-a-half percent, 3.75%, 3.8%, 3.85%, 3.851%. And I have had teams that are doing that and they’re coming to me and, “Look. The numbers are up and to the right. It’s going up.” It’s like, “Well, that’s true but are we going to make it to 10% or have we hit the point of diminishing returns?” And obviously, we hit the point of diminishing returns. Maybe want to consider a pivot at that time. That’s the flavor of innovation that counts. Establish a baseline to the engine, pivot or persevere.

Bernhard Kappe: So, you mentioned vanity metrics and actionable metrics. Can you give some examples of vanity metrics and take one of the growth approaches? What would, say for the same, what are appropriate actionable metrics?

Eric Ries: So, these are new vanity metrics. Vanity metrics are the numbers you put in your press release to make your competitors feel bad. It’s like, “A hundred billion hamburgers served,” or like, “Our platform has had 30 million messages sent,” and make sure the competitive CEO got his CT under. “How many messages have we sent?” They’re like, “I don’t know. We got a probable. We got tons of customers. They love our product.” It’s like, “Well, how many messages have we sent?” It’s like, “We only sent 87,000, but they’re each worth a hundred dollars. So, is that okay?” It’s like, “I don’t know. He got 10 million messages.”

Think about it. 10 million messages. What do you know about their business? Could it be 10 million people tried the product once and churned out? Or it could be one guy with a really exciting web browser. That’s how we were aware of the tech march, so you could seem like you’re being successful without revealing any actual information about your business. Now, why TechCrunch is willing to print them, different conversation for the journalism school. For our purposes, I’m fine with you using vanity metrics to make your competitors feel bad. It’s a time-honored technique. Love it.

But what happens when you start to breathe in your own exhaust and believe your vanity metrics as if they matter? Well, here’s what happens. Let’s say the vanity metrics go up. I can interview any person in your organization and ask them what causes numbers to go up and I already know what they’re going to tell me. They’re going to say, “Well, it’s the thing I was working on at the time.” So, if I hear your engineers, I’ll be like, “Well, we launched these awesome features last month and this month, the numbers are up, so QED.” And I can say something like, “Interesting. I have an alternate theory. My theory is that Mercury was in retrograde last month and I believe in astrology, so I heard that Mercury causes numbers to go up.”

And most engineers I say that to, I’ve done this many times. I sometimes fear for my life because they’re mad, like, “How dare you compare what I do to astrology.” I’m like, “I’m not the one making the comparison. I was visiting but you live here and neither of us has a clue what causes these numbers to go up, especially if I go introduce someone in marketing. They’re going to say, ‘Oh, well. It’s a great marketing campaign. That’s why the numbers are up.'”

What happens when the numbers go down? Is it the same thing? Oh, no. Now, it’s somebody else’s fault. “We need these great features in engineering. Those idiots in marketing ruined it.” So, maybe metrics allow teams, so everyone gets to live in their own private reality where the stuff they do matters and the idiots down the hall are always sabotaging it. And is it any wonder that it develops like factional interdepartmental warfare? Well, no. We can’t even agree on a fact of what’s going on.

So, the alternative, we call it actionable metrics, which are data that shows you what you would have to do to get more of it and it tends to be cohort or A/B split testing-type data. So, imagine I show 50% of my customers version A of a product and 50% version B and I say, “Okay. Which one has higher engagement?” Well, it doesn’t matter if we got a press mention that day. Doesn’t matter what’s going on because people were randomly distributed between the two groups. It’s an actual control trial in scientific terms.

So, the plea is what are the actual metrics? And in the book, I lay out for each of the engines of growth what I think the numbers are. For an engagement-type business, we can tell that the feedback loop is working by simply taking our natural word-of-mouth growth rate. Let’s say it’s 5% per month and we grow naturally, because customers love our product. And so, track our monthly churn rate. So, what percentage of customers did we lose?

Let’s say our churn rate is only 30%. We have a 70% retention rate. That’s awesome, right? Well, no. Not if we have a 5% natural growth rate because it means we’re getting negative 25% growth month over month. So, the safety engine of growth, all it cares about is what I call the rate of compounding, but natural growth rate subtracted from churn rate. If that’s our business, then we want to focus all of our energy on drying that churn rate down so that we can get these compounding interest effects. If I get to a hundred percent retention, then 5% a month compounding interest is going to be pretty exciting. Wouldn’t you like an omega count that grew 5% per month compounding? That’d be pretty sweet. So, each of the agents of growth have a framework like that that allows you to, if you do it right, get that super linear growth that gives you the cool hockey stick shape.

Bernhard Kappe: You’ve obviously been mentoring a whole bunch of startups and entrepreneurs within larger companies. What would you say are the biggest startups? This isn’t easy if you’ve been doing things in a different way then are there some particular aha moments that particularly people there really have?

Eric Ries: Yeah. It is hard. It is a different paradigm for work. And so, anyone who’s had any success at all in their career is at a major disadvantage because they probably had that success in a different paradigm and it’s hard to unlearn something that worked for you before. I think most of the most devastating mistakes have that planning fallacy at their heart, that we just know the entrepreneur that wants to spend years in stealth mode building an amazing product and then launching it in the premise, which I’ve done that many times, never successfully.

They fundamentally believe that they know what customers want. And so, they can plan what’s going to happen which … Think about it. That’s someone who’s saying, “I can predict the future.” Normally, when you go like, “I can predict the future,” people lock you up in a mental institution. “What do you mean you can predict the future? Nobody can predict the future. It’s impossible.”

But if you’re an entrepreneur, they go, “Oh, it’s okay.” And the reason is that we use power as entrepreneurs. One of the optimal super powers is what I call the reality distortion field. And this is a term originally coined to describe Steve Jobs. And if you have the power of the reality distortion field, that means that you can convince people in your vicinity to believe things as if they were true that were not strictly speaking actually true. And that’s great. It’s really good for improving productivity and morale, and getting people excited. It’s a really awesome bit of entrepreneurial sleight of hand. It’s like we know what customers want.

Well, actually what I mean is that when we finish building this awesome thing, customers will want it in the future. Is that exactly the same as we know what customers want? No. It’s actually strictly different. This is, I hope and pray I know what customers want. Might want, maybe, but we believe.

And there’s nothing wrong with the reality distortion field. It’s just there’s another group of people who have that power and we call those people crazy people. If you’re a sociopath and you run a cult, it’s super helpful to have the power to get people in your vicinity. Think about it. It’s a belief as if it were true. They’re not, strictly speaking, actually true.

So, if you or maybe you have a friend, if your friend is in the midst of a reality distortion field with an entrepreneur, how do you know if the entrepreneur is a brilliant visionary, the next Steve Jobs. They wear a black turtleneck, so they look good. Or either you’re calling a crazy person who’s going to accomplish nothing. And your friend’s sake, all I’m asking you to do is double check. Probably, the vision is a hundred percent right and your product is the best thing since sliced bread. It’s as good as teleportation. Teleportation would be a great product. Maybe working on teleportation like, “Yeah. You go work on that right now. Really looking forward to it.” Who wouldn’t want teleportation?

Most entrepreneurs think that’s as good as their product is and then I think about having that belief, it’s actually very easy to test. If my product is teleportation, I’m going to get a hundred percent conversion rate, every customer I talk to, like, “Hi. Would you like to give me $5 to teleport instead of commuting?” Everybody’s going to be like, “Yes. Get me that right now.” Excellent. Your product is that good. That produces nice, falsifiable figures. Let’s talk to 10 people. Obviously, all 10 of them will be like, “I love your product. Can’t wait to get it.” And if that doesn’t happen, doesn’t mean we give up. Doesn’t mean we abandon the vision. It just means, huh, maybe there’s something not quite right here. Maybe a little bit more investigation would make sense. So, like I said, “You’re probably right, but let’s double check.” What’s the worst that can happen?

Bernhard Kappe: So, then, what about some aha moments? Where are those aha moments?

Eric Ries: The best aha moments are the expensive and humiliating failures, honestly. I mean, we cannot … We came into IMVU after having built a company that spent five years and $50 million building a product that self-loaded. Launched it in the press to rave reviews and then have no customers. The company became a defense contractor. It was terrible. If that had happened to us, we probably would have thought, “That works,” because that’s what you read in the movies and what you see in the press.

So, that’s the big aha moment for most people if you have to put your team in a position to fail, because failure is the origin of all learning and that’s why we make these predictions. That’s why we try to be specific about what’s supposed to happen, not because they’re actual plans. You have a great designer on your team, they’re going to want to make a customer persona and tell you all about what the customer’s going to want. And that’s great. That’s a really good skill and there’s a whole Lean UX now. It’s really excellent. Design is a very important skill for doing this. All you need to do is say, “Excellent. Thank you for that customer persona hypothesis. Now, let’s go find out if it’s true.”

What would be true if this is a correct and accurate description? What would be true is it’s all, like when we built IMVU, we thought our product customers were going to be stay-at-home moms who wanted to play our online games and that’s the people who play 2D casual games, our same market. And when we would test our product, our early adopters were all teenagers. And I remember, IMVU was a communication product so we could use it to communicate with our customers, so we do this thing called chat now. It would randomly match you with customers and I would sit there and be like, “I need to talk to customers. That’s important. I know it’s what I’m supposed to do,” so click the button, talk to my target customer and boom, teenager would come on and be like using LOL and all these acronyms I don’t understand. I’m like, “Damn it! Get out of my way. I’m trying to talk to our customer and you’re clogging up the pipeline.” Close out, get a new one on. Another teenager. “Jesus Christ!”

Because in our business plan, it said, “You don’t want a teenager. It’s really hard to extract money from teenagers. They have no credit cards and so on.” And oops. They turn out to be our customers. And eventually we had to be like, “Oh, that reality. Good.” Probably we should adapt ourselves to what’s real instead of making stuff up. So, that was a pretty big one.

Bernhard Kappe: So, yeah. What are the customer relevance key insights for me has always been get out of the building. If you bring that back to the lean manufacturing approach, which is sometimes when I say that, that is equal and different. First, you say, “What?” Then you translate it as either go to the source or go find out for yourself and where do you go find out? It’s with the customer. That’s where the path starts. So, how do you talk to customers? How do you go about figuring out what they want?

Eric Ries: Let’s start with the number one thing not to do, which is to ask customers what they want. That is a waste of time and here’s why. Human beings have a psychological bug in our makeup that makes us genetically incapable of saying how we would behave in hypothetical situations. Even one as simple as how will you feel about lunch tomorrow? Just the academic research on this is very clear. People just don’t know. Now, imagine how accurate can they be when you’re like, “Do you think you would want to buy this hypothetical thing that I might make in the future and kind of vaguely describe to you?” Whatever they say is total garbage.

So, if you’ve ever worked with a visionary co-founder or person in your company, you’re going to be like, “Hey, let’s test this stuff with customers,” and then, you’re going to be like, “But customers don’t know what they want.” And that’s true. Customers don’t know what they want but electrons don’t know what they want, either. And we can still do science, because the goal is to figure out how do we put people into a behavioral situation where we can have our ideas validated or invalidated and that often requires us to act indirectly. So, instead of walking in, we have like, “Do you think you would want to buy this thing?” One of the techniques, for example, that Steve recommends in his book is he walks into a customer and tries to sell him something. “I would like to sell you this thing that I already made.” The fact that you haven’t made it is totally beside the point because the only information the customers have is what you tell them.

So, if they’re like, “Yes, thank god. I can’t wait to give you my purchase order. Here it is.” Then, you can apologize. “Listen. It’s not quite ready but now you’re on the pre-order list and I promise you’ll get it first.” But guess what. That’s not going to happen. You’re not going to have to apologize because, of course, you’re totally wrong. Not you, but the person next to you is totally wrong about …

So, that’s the key. How can we make an experimental condition that can help? And one of the techniques is what we call the magic test. Before you sell your product, try selling the magic version, which is just now you put a landing page on the internet and it’s like, “Are you a customer that has this problem?” Blah, blah, blah. “Wouldn’t you like to have that solved for only $9.95? Click here,” you say, “Yes,” and go into it. Now, if you can’t sell magic, you definitely can’t sell your product, because your product is not as good as magic. I’m sorry. It’s not. Close but not as good. So, why not just check it out?

Another variant on that for people who can’t quite handle the magic test is what we call a concierge MVP. Tell a story of a company called Food on the Table in Austin, Texas. And is founded by someone who worked with me in IMVU, so I know their story really well. They wanted to build an algorithmic recipe and menu planning service for parents. This is really cool. It figures out what’s on sale at your local grocery store, knows what your kids like to eat and don’t eat and knows your dietary restrictions, knows the recipes that you like to use at home, knows what gives you an optimized shopping list and then automatically suggests new recipes their professional chef suggested. It basically helps you optimize your menu planning.

So, that’s a pretty complicated product. He and his technologists, when they started the company, did not build a single line of software. They went to their local grocery store and they did Genchi Genbutsu, which is to meet customers, see how they observe and talk to them. But they did a twist on it, which is that after they would talk with customers, they said, “Oh, that does sound kind of interesting.” They were like, “Great! Would you like to buy this service from us?” And they’re like, “What do you mean?” It’s like, “Well, if you say, ‘Yes,’ we will come to your house once a week. We will give you the menu plan and talk to you and you can modify it. We’ll have our professional chefs do all these recipes and then we will collect a check from you for $9.95. Does that sound good to you?”

Now, most people are like, “No. It does not sound good to me. No, thank you. You’re not coming to my house.” But that’s fine because an early adopter is someone who’s like, “God! That would be so great. I’d be willing to tolerate this kind of weird delivery queue.” And so, you give that first customer the concierge treatment, the best possible version of your product and then you try to get a second customer. So, they may pay you. And a third and fourth. And by traditional standards, it’s wildly inefficient. You’ve got the CEO and the CTO of this company wasting their time manually making recipes for people, and handing them, going driving to their house.

Well, the time you invest in technology is when they have more customers than they can physically handle, which actually took a surprisingly long time because, of course, they were wrong about too many elements of the product. And so, think about it. You’re a technologist, you’re a software person especially. Think about how nice it would be if every time you have to build something, you were always refactoring in existing workflows that you already knew worked and you never had to work speculatively. That’s what we call spec, speculations.

So, what if we didn’t have any speculation? What if we always knew exactly what to build? Wouldn’t that be a lot more likely to be successful? Well, in the concierge MVP, you always were in that situation. So, give that a shot.

Bernhard Kappe: Our speaker in September last year, Mike Evans from GrubHub, described what they did, they really started out with a Concierge MVP. There was a lot of scrambling and calling up the recipes. So, it’s definitely great to meet you as well.

At some point, I think you talk about how the runway company ends and really measuring how many pivots you can do within a certain time period, if that’s really critical measures. Can you talk a little bit more about the gold measure life loop and how you worked with that?

Eric Ries: Absolutely. One of the key insights of lean manufacturing is being able to focus on the fundamental cycle time of the business and lean manufacturing cycle time is how much time it lapses between when we start working on a product and the customers pays us money for that product. We want to make it as soon as possible. And now the analogous thing for lean startups is, since we don’t know who the customer is, we want to discover who they are and what they want as quickly as possible.

So, we have this concept. We call it build, measure, learn. Three step feedback loop. That’s our fundamental loop. We take ideas. We turn those ideas into products. We measure how customers respond and then that allows us to influence our next set of ideas and every bit of advice, every process question, every infrastructure decision should be measured against what will help us get through this loop faster.

Another really irritating thing about startup advice you’ve probably heard is it’s totally self-contradictory. When I was an entrepreneur, I would go, maybe have one advisor who would be like, “Make sure you really work on scalability, because you don’t want to be the next Friendster, have that high profile scalability problem.” Like, yeah. Scalability is so important. And the next five, you’ll be like, “Well, also don’t worry too much about scalability because Facebook didn’t worry about scalability and they did it just fine. So, if they waited, it would have been terrible.” I was, “Okay. Don’t worry about scalability.”

Also, really make sure you have good design, because we all know that Steve Jobs never shipped a product that wasn’t really beautiful and perfect and obviously good design is really important. It’s like, next advice. “Well, you know, Craigslist and eBay, these products did really well and that design still sucks.” So, product design isn’t that important. It’s like, scalable and not scalable design and no design. Just go down the list. For every technique, I can find you someone who did it, didn’t do it, was successful in their unit, 2×2, four possible outcomes. It’s a disaster.

So, we need a heuristic for figuring out if it is a good idea? Do we need to invest in scalability right now? Well, the only question you have to ask is is it slowing down our ability to learn, that we’re not scalable, we have only one customer. Well, you don’t have a scalability problem. So, it’s fine, unless that customer really likes our product.

So, what is a pivot? I said it before. A pivot is a change in strategy without a change in vision, but how do you get to the moment of pivoting sooner? You can’t get there by just building stuff more efficiently because the most efficient way to build is in large, long, giant backsides. The most fun time in a startup’s life is when you have no customers. It’s awesome. The engineers love that. Just heads down, crank, crank, crank, crank. No worry, no pesky customers. And you’re like, “Ah. I don’t really like that.” Everything always goes exactly like you plan when your cell phone is free.

So, we can’t just measure stuff. We don’t optimize for that because we have data analysts on your team, you have 10,000 graphs, you can’t learn anything from 10,000 graphs in what I call the NBA fallacy we already talked about. I can learn tons of stuff at the whiteboard, this vast iterate all by myself where there’s no facts so it’s no good.

So, if you think about startup runway, how much time do we have left before we crash? It’s usually defined as burn rate, the amount of money we have left divided by burn rate, so we have 10 months left before we run out of money, but I think the correct way to measure it is actually how many opportunities to pivot do we have, because that’s what really matters. How many more swings of the bat do we have? How many more strikes do we have before we die? And if you want to extend the runway, you could raise more money or you could get to the pivot moment a little bit quicker. And the cool thing about that is even a 10% improvement in your cycle time might give you 10 more iterations because you keep doing it over and over again, so it has a nice compounding effect.

So, whenever possible, whenever we’re going to make an investment in infrastructure and process, we’re going to invest in stuff that accelerates our ability to learn. And therefore, if you want a winding startup to be more capital efficient, it’s exactly for that reason. They can extend right away without raising more money.

Bernhard Kappe: So, I’m probably going to open this up to questions from the audience in a little bit but obviously a lot of good things have been happening of late with your book and think I saw a tweet that someone saw a copy of Inc. Magazine with you on the cover.

So, what’s this been like the past couple weeks and what’s next?

Eric Ries: It’s just so weird. First of all, I’ve been criticizing startups who are all trying to get on the cover of magazines all the time, and I always say things like, “Oh, you don’t want to do magazines, vanity trip. It’s not important. Don’t launch.” So, now, I guess I’m on the cover of Inc. magazine this month.

So, I don’t think of that exactly.

But the reason I wrote the book was we need to reach the people who are causing the problem. And who are those people? There’s more entrepreneurs than ever and the entrepreneurs generally get this and are eager to do things as efficiently as possible. They’re not the problem. The problem is all the people who hold entrepreneurs accountable, who invest in entrepreneurs, the CFOs and the VCs and the private equity people, the whole rest of the ecosystem. Those people are never going to read an entrepreneurship blog. Most of those people don’t even think they are entrepreneurs. Not going to read some startup lessons learned tech things.

If we want to reach those people, if we want to stop them from causing the problem, we have to figure out how to make them interested in reading about this thing that we all think is really exciting. Hence, for better or worse, books, mainstream published books are specifically how you reach those people. And it’s not just any books. It is a very specific class of books, namely bestsellers. And here’s the really weird thing. There’s a huge chunk of people, especially in business that only read bestsellers but those are the people who you need to buy the book in order for it to become a bestseller. So, a classic chicken-and-egg problem.

For people in publishing, this level of uncertainty and confusion is very daunting and causing a lot of chaos, but I’m an entrepreneur. I’ll say, “Well, I shouldn’t get into this confusion.” It’s very straightforward. We need to work backwards from what we need to accomplish to what we need to do. Well, how many copies do we actually have to sell to become a bestseller? And so, I spent the last year. Some of you who follow me on Twitter are sick and tired from all the crazy marketing experiments and pre-order campaigns and bundles. I actually done 10 of those things, constant split testing and all kinds of insanity, just to try to figure out what would it take to get our early adopters, you guys, to do something that’s really fun and mentally crazy, which is to buy a book before it comes out, because why would you do that? Why don’t you just wait to see if it’s any good and buy it then? Now it’s a lot more logical thing to do but we want you to pre-order so that the book will debut as a best seller so that it will reach all these other people.

And so that is what I have been working on and I’ve been in the future for so long, I actually would like my life as a black hole and then all of a sudden, there’s all this media interest and all this excitement because actually I just found this out, the book is going to debut as a bestseller.

If you open The New York Times, the hard copy New York Times, not this Sunday but a week from Sunday, you will have to find a business section. Oh, there’s no business bestseller list. Business books, by the way, are not considered non-fiction. They are considered advice and how to.

So, the three big new books that were launched at the same time as this book were Lean Startup, the 2012 edition of the Guinness Book of World Records, and a new book by a televangelist whose name I’m forgetting who has a TV show that seven million people watch every week. So, he’s going to be the number one bestseller, because did I mention seven million people watch his show, but if you go to that paper, we just got the news that the Lean Startup will be number two. So, we will be the number two bestseller in the category.

Don’t give me a hand. Give yourselves a hand. You guys bought the copies that made it happen. All I had to do was write it. In fact, so far, its success is based in 0% on the quality of the content of the book. The really important work begins now because now we have to put the book down. Now that we’ve made it a bestseller, it has the legitimacy to go to these places that currently would never have been able to get this message to. And so, now, we’ll find out if the content is any good and those people read it and find it helpful. So far, early indications are yes.

So, for those of you who feel like Lean Startup is overhyped, just FYI, you have not seen anything yet. What is coming is going to be ridiculous because I believe we are having a real crossing the chasm moment. We are about to take this idea from a fringe thing that happens in startup clubs to an important business mainstream idea and if you read the Financial Times just reviewed it and said it was one of the important business books of the year.

Inc. Magazine just did this big spread. If you listen to Morning Edition on Monday, they do four-and-a-half minutes on the book. It is about to get the kind of media attention that is pretty absurd. I’ve been on cable news. I’m going to be on both Fox News and MSNBC on Friday, so I don’t know what to do exactly there. If anyone has thoughts about Obamacare, I’d love to have some talking points.

And for me, this is so weird. Do you remember when I said I programmed computers for a living? Hey, I like to be in my basement in the dark at 2:00 a.m. hacking and now I’m doing this. So, it’s a very strange and actually very humbling thing. And the thing that is so humbling about it is they put my face on the cover for some reason, but like I said, you guys do the work.

So, the fact that you were willing to take that leap of faith and not just do the work and buy the book and tell your friends and evangelize and be on social media. Just, it really means a lot to me because it means that you take this idea seriously and that ultimately is what this is all about. So, thank you all so much.

Bernhard Kappe: Thank you. Now it’s time for some questions. I think we have two hashtags. And they will intersperse some from Twitter.

Eric Ries: Awesome. Awesome. Thank you.

Bernhard Kappe: So, for those of you who are watching, the Twitter hashtag is #LeanStartup and #Chicago.

All right. Who has questions?

Related Posts

Article

How nen DTx Will Help Kids with Cancer to Manage Pain

Article

How Industry Experience Shaped Creation of DTx Startup nen

Article

Faster Feedback Before Development Starts: Feasibility

Article

Lowering Risk Using Agile and Lean Methodologies